While searching the garage the other day for a baling hook, I found a box titled “old hearing aids.” I wondered how old some of these might be, and if there were any interesting features/design characteristics. And, why did I keep these?

A number of photos of old hearing aids can be found in the literature, but usually don’t provide enough information to show the ingenuity that went into some of them. Some are just interesting enough either because of the technology involved, or just because they are rare, that it would be unfortunate to circular file my old hearing aids before providing information somewhere on them.

I did find old hearing aids and some that were interesting. This post describes a few of them and shows where they fit into the historical development of hearing aids. This was done without going into a full search of the companies who manufactured them, knowing that most of them no longer exist. But, these were the cream of the crop in their hay day! (No pun related to the baling hook). These are hearing aids people actually wore, not experimental models.

This, and perhaps a couple of posts that follow, will feature some of these products and try to put them into their historical perspective.

Hand-Held Hearing Aid – The First PSAP?

Aurex “P-A” (Personal Amplifier) 1948

This was a 3 vacuum tube, hand held amplifier with a rubber eartip encased in a small trumpet-like device (Figure 1).

It was powered by two batteries (RM-3, 1.4 volt mercury “A” battery and a 15 volt No. 411 “B” battery). It was advertised as useful for normal hearing persons at concerts, etc. Dimensions were 114 mm long x 38 mm in diameter. An On/Off switch combined with a volume control was just below the upper golden rim. The microphone was at the bottom of the device and covered by a felt material. I suppose that this could be called a precursor to current day PSAPs (Personal Sound Amplification Products) based on the recommended use. It was advertised for use at concerts by people with normal hearing, but certainly would have helped hearing-impaired individuals as well.

Figure 1. Aurex “P-A” (Personal Amplifier). It was advertised for use at concerts by individuals with normal hearing, but certainly would have helped those with hearing loss as well.

Aurex was established in Chicago in 1935 by Walter Henry Huth. Aurex manufactured group hearing aids, and in 1939 their first wearable hearing aid. They produced early sub-miniature vacuum tubes, and were one of the first companies to use “prescription fitting” by making use of a series of switches in the hearing aid.

1950s – Introduction of Three New Types of Hearing Aids

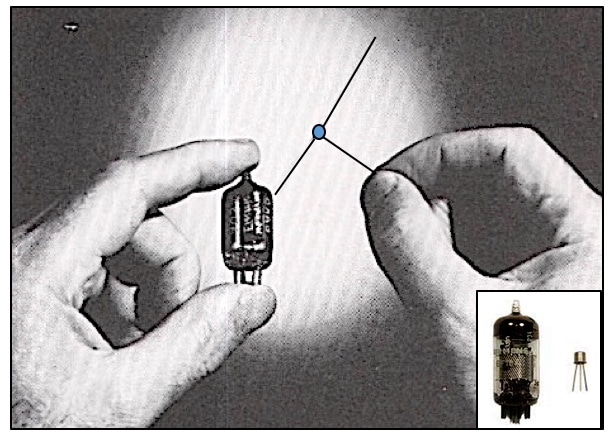

Electric body-worn hearing aids dominated the US (and other parts of the world) market for many years until about the mid 1950s. Early models used vacuum tube amplifiers, and required an “A” battery (to activate the vacuum tube), and a “B” battery (to provide the necessary amplification). These required rather large voltages, especially the “B” battery.

Figure 2. Comparison in size of vacuum tube (left) to transistor (right). This, along with the other advantages of transistors, contributed to size reduction in hearing aids.

However, all this changed with the introduction of the transistor amplifier in the early 1950s. These were very small compared to vacuum tubes and required only a single battery having much lower voltage, meaning that the power supply was smaller as well (Figure 2). Body-worn hearing aids were among the first to use transistors (starting in about 1953), and with this, hearing aid evolution took a major step forward. The 1950s saw the introduction of eyeglass, behind-the-ear, and in-the-ear hearing aids (in that order) – all resulting from the use of transistor technology.

Body-Worn Hearing Aids

Still, prior to, and even into the early part of the transistor era, body-worn hearing aids showed continued improvements, primarily in size and power supply reduction. It helped that the microphone and receiver/speaker were being reduced in size as well. I found many models of body worn hearing aids in the box. It would require too much space to feature all of these. Therefore, I decided that I would feature just a couple that were truly different.

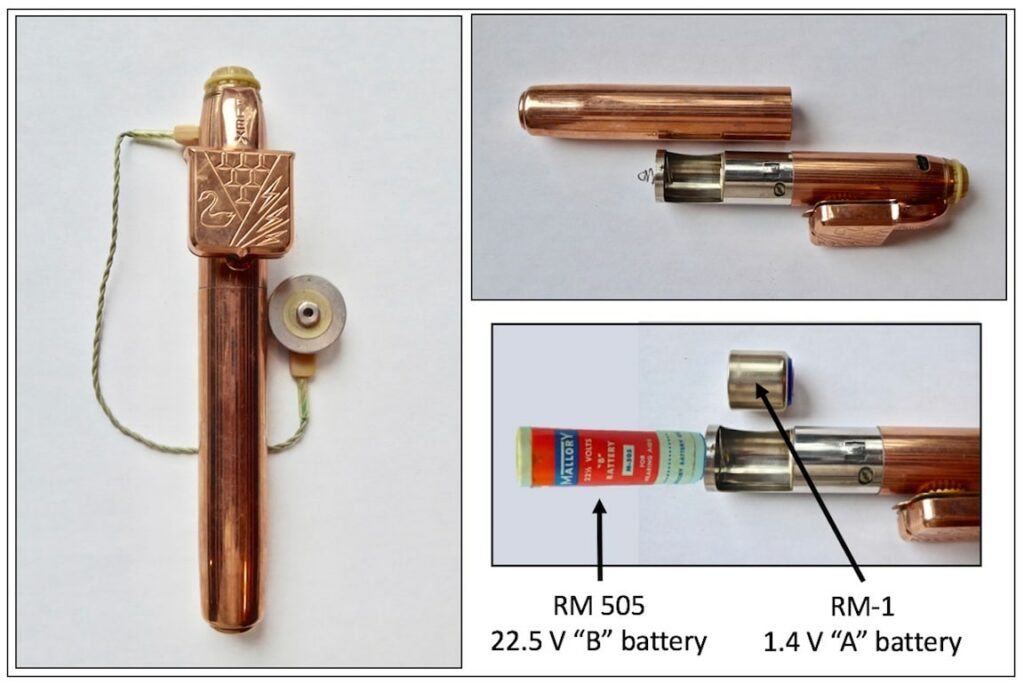

Telex 300 (1950)

This 1-piece pen-style hearing aid (prior to the transistor), was essentially a body-worn hearing aid disguised as a fountain pen (Figure 3). It housed 3 vacuum tubes, used a printed circuit, and was powered by two batteries (RM1 and a 505). The case was made of metal, 140 mm long and 18mm om diameter. Weight was 2.5 oz. without the batteries. The microphone was on the pocket clip, the volume control was on the top, and a two-prong cord delivered the amplified signal to the ear via an external receiver. An ad for the new style hearing aid is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Telex Pen-style hearing aid using 3 vacuum tubes. The microphone is incorporated into the clip-on attachment on the upper part of the aid.

Telex was established in 1936 in St. Paul, Minnesota by Allen Hempel (previously with Acousticon and Aurex) as Telex Products Co.

Eyeglass Hearing Aids

Most hearing professionals have only a vague idea about eyeglass hearing aids and believe that they were little used. This is quite to the contrary. In fact, Sam Lybarger has indicated that eyeglass hearing aids preceded behind-the-ear (BTE) amplification devices and were developed independently1. From about 1954 until the mid 1970s, eyeglass hearing aids had a reasonable share of the hearing aid market, especially replacing some body-worn aids during the earlier years of this time period.

With the employment of the transistor, eyeglass hearing aids served as an independent step between body-worn hearing aids and BTE products. A discussion of how they served this role was the subject of a previous post. Eyeglass hearing aids lost favor for a variety of reasons, but primarily because of the expansion of lightweight eyeglasses. It became essentially impossible to inventory all the styles, hinge varieties, colors, etc. for frames and temples.

I recall in about the mid 1970s, at Audiotone, we threw out thousands of hinge adaptors because none fit the newer thin frames of hearing aids and the decision was made to design no new eyeglass hearing aids. Amplification could be better managed without such complications using BTE units.

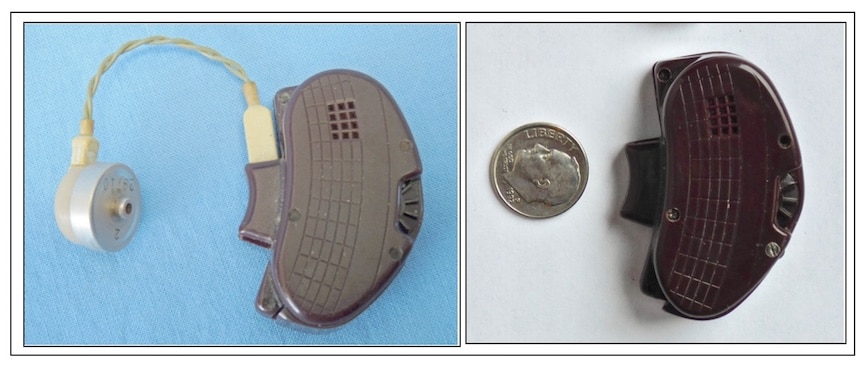

Barrette Hearing Aids

These units served as a step between body-worn hearing aids and behind-the-ear hearing aids. These were essentially body aids worn somewhere in/on the hair (primarily of women). Even after transistors were used in hearing aids, such units continued to use external receivers, as shown in Figure 5. The unit in Figure 5 is unidentified except for a serial number: 13250. That it used a 625 cell indicates that it was a transistor hearing aid of the mid-to-late 1950s.

Figure 5. Barrette-style hearing aids served as a step between eyeglass transistor hearing aids and behind-the-ear hearing aids. They essentially incorporated the features of body-worn aids and an external receiver, which was connected by a cord (receiver not shown in image).

Sonotone 79 (1955)

This hearing aid was used either as a barrette or BTE hearing aid according to Sonotone (Figure 6). It used an external receiver. It was a 3-transistor amplifier and was powered by a 625 cell. The case was plastic, with dimensions of 46 x 32 x 16 mm. Sonotone suggested that this might represent the first behind-the-ear hearing aid2.

However, because the receiver was detached and not integrated into the housing, this author is more likely to place it into the Barrette/body-worn category, but one that made the transition from vacuum tubes to transistors. The fact that it is difficult to imagine this being placed behind the ear, with the receiver cord attached on the left extended portion, makes it difficult to imagine this as being a true behind the ear instrument – other than attached somewhere to the hair behind the ear, and then the cord going to the ear.

In reality, this is a barrette hearing aid.

Figure 6. Sonotone 79 transistor hearing aid of 1955. Sonotone promoted it as a barrette-style hearing aid, but they also left open their belief that this might be the first behind-the-ear hearing aid. The cord arrangement to the left side of the instrument would seem to make it difficult to fit behind the ear. It is basically a barrette hearing aid. Not shown is the barrette attachment on the back side. The cord could be attached either at the top or bottom of its attachment to the aid, depending on the ear to which it was fitted.

Next week’s post will continue this theme, showing the initial true behind-the-ear hearing aids.

References

- Lybarger, S. (1989). Unpublished presentation at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, March 25.

- Berger, K. (1970). The Hearing Aid and its Development. National Hearing Aid Society, Livonia, MI.

Wayne Staab, PhD, is an internationally recognized authority in hearing aids. As President of Dr. Wayne J. Staab and Associates, he is engaged in consulting, research, development, manufacturing, education, and marketing projects related to hearing. His professional career has included University teaching, hearing clinic work, hearing aid company management and sales, and extensive work with engineering in developing and bringing new technology and products to the discipline of hearing. This varied background allows him to couple manufacturing and business with the science of acoustics to bring innovative developments and insights to our discipline. Dr. Staab has authored numerous books, chapters, and articles related to hearing aids and their fitting, and is an internationally-requested presenter. He is a past President and past Executive Director of the American Auditory Society and a retired Fellow of the International Collegium of Rehabilitative Audiology.

**this piece has been updated for clarity. It originally published on September 12, 2017