“Peeling the Onion” is a monthly column by Harvey Abrams, PhD

I concluded last month’s post by describing The Chronic Care Model (CCM); Wagner, 1998) which consists of six components considered critical for improving outcomes among patients with chronic health conditions:

- Self-Management Support

- Delivery System Design

- Decision Support

- Clinical Information Systems

- Organization of Health Care

- Community

Assuming you bought my argument that adult-onset hearing loss can (or should) be considered a chronic health condition, I’d like to explore the model further to determine if the techniques that have been successfully used for such conditions as diabetes and chronic heart failure might apply to hearing loss management.

Internal Triggers for Chronic Conditions

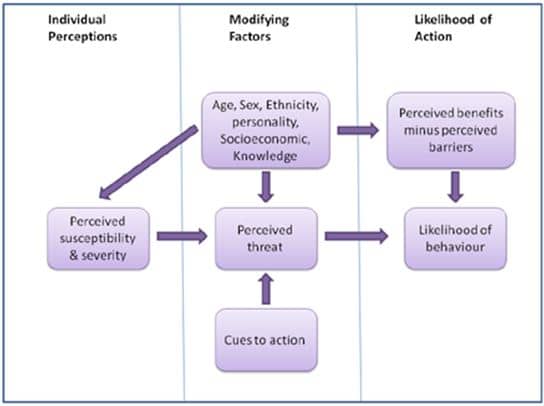

Figure 1. The Health Belief Model Flow (source Glanz et al., 2002){{1}}[[1]]Glanz K, Rimer BK & Lewis FM (2002). Health Behavior and Health Education. Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco: Wiley & Sons.[[1]]

But there is, in fact, a model that explains when and why someone takes action to get care. It’s called the Health Belief Model (HBM) (figure 1) which was proposed in the 1950s by social psychologists at U.S. Public Health Service to better understand why so many people failed to get screened for tuberculosis despite the widespread availability of screening programs{{2}}[[2]]Shaw, A. (2012). The health belief model and social marketing. Strategicplanet.com[[2]] The HBM model suggests that the ultimate decision to take action is the result of a subconscious (for the most part) calculation of a number of factors including:

- one’s perceived susceptibility and severity of a specific condition

- modifying factors such as age, ethnicity, knowledge of the disorder

- cues to action, and the perceived threat

- perceived benefits minus the perceived risk

My Personal Triggers

Let me give you a personal example. For the past month I’ve been having pain in my pelvic area that radiates down my leg. I’m a life-long runner, so occasional aches and pains are not unusual and I often take a break from running and substitute another aerobic activity such as biking.

After a month, however, this particular pain not only persisted but got worse. I made a judgment regarding my susceptibility to a joint-related injury (many decades of running) and its severity (moderate to severe). I had knowledge about sports-related injuries and the conditions that could be causing the pain and concluded that it would not likely resolve without seeking medical care (the persistent pain being my cue to action). I calculated the likely benefits (resolution of the pain) and the barriers (I have good health insurance so cost was not a concern and, while I distrust the Medical-Industrial Complex, the healthcare facility I chose was affiliated with my university and one block from my office). So, I took action.

Our Patients’ Triggers

What I’ve described above for myself as an individual is the calculus that each of us often goes through before we visit a healthcare provider. So how does this work with someone with a hearing loss?

Think about the patients whom you see in your practice. How might the HBM apply to them? Why does Mr. Smith call to make an appointment for the first time? Likely (and subconsciously) Mr. Smith has taken this action on the basis of the factors described in the model:

- He has determined a certain level of susceptibility to hearing impairment (age, noise exposure);

- He has determined a certain degree of severity (asking spouse to repeat or having to turn up the TV);

- He has some knowledge of hearing loss (experience of friends);

- He is cued to action by the complaints of his wife;

- He perceives a threat (continued tension with wife);

- He calculates the benefit (confirmation of problem or, alternatively, confirmation that he doesn’t have a problem and, in fact, everyone is mumbling); and

- He determines that those benefits outweigh the barriers (cost of the examination, getting to the clinic, being pressured to buy hearing aids).

Note that Mr. Smith’s action here is making an appointment for a hearing evaluation; he’s NOT making an appointment to purchase hearing aids. That decision requires an entirely different internal HBM calculation – particularly the part about barriers. Here, the perceived barriers (cost, stigma) may very well outweigh the benefits of whatever help he perceives hearing aids will provide. As most of you know, if a patient is pressured to purchase hearing aids (by family members or the professional) things are not likely to end well.

The Hearing Beliefs Questionnaire

The application of HBM to hearing health behavior is not entirely theoretical. Dr. Gabrielle (Gaby) Saunders of the VA National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research has conducted research supporting the model as it influences hearing aid uptake and utilization. Dr. Saunders and colleagues (2013){{3}}[[3]]Saunders, G., Frederick, M., Silverman, S., Papesh, M. (2013). Application of the health belief model: Development of the hearing beliefs questionnaire (HBQ) and its associations with hearing health behaviors. International Journal of Audiology 2013; 52: 558–567.[[3]] incorporated the principles of HBM into the development of a hearing beliefs questionnaire (HBQ). The results of their research suggest that HBM is, in fact, applicable to hearing health behaviors and that the HBQ can help the clinician assess their patients’ hearing health belief and predict their hearing health behaviors.

As interesting as the HBM is, it is merely another layer of the onion that we need to peel back. When we do, we shall see yet another model – the Transtheoretical Model – that may help to explain where our patients are along their hearing healthcare journey and how we might use that information to better customize our management strategies. More about that next time.

This is Part 4 of the Peeling the Onion series. Click here for Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 5.

Harvey Abrams, PhD, is currently Principal Research Audiologist at Starkey Technologies. Dr. Abrams has served in various clinical, research, and administrative capacities with Starkey, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense. Dr. Abrams received his master’s and doctoral degrees from the University of Florida. His research has focused on treatment efficacy and improved quality of life associated with audiologic intervention. He has authored and co-authored several recent papers and book chapters and frequently lectures on post-fitting audiologic rehabilitation, outcome measures, health-related quality of life, and evidence-based audiologic practice. Dr. Abrams can be reached at [email protected]

feature image by Ross Land/Getty