“Peeling the Onion” is a monthly column by Harvey Abrams, PhD.

In last month’s post, I discussed the influence of our profession’s early history on our current self-perception of audiology as a medical model of care and suggested that we may want to consider reframing our profession as a rehabilitative discipline. In fact, there are other possible models for us to consider in addition to the medical and rehabilitative ones:

- The optometric (intuitive) model: Audiologists correct for hearing loss the way optometrists correct for vision loss. In fact, the first iteration of the Songbird hearing aid was developed by Johnson & Johnson and marketed as a “contact lens for the ears.” More recently developed hearing technology brings the contact lens analogy much closer to reality.

- The orthodontic (restorative) model. The auditory system changes in response to a hearing appliance similar (in concept) to how the teeth and jaw change in response to an orthodontic appliance. This is a compelling idea: patients return to the orthodontist for adjustments to their appliance in order to meet a targeted cosmetic goal in the same way patients should be returning to us for adjustments to the hearing aid parameters to meet a targeted audibility goal.

Defining Rehabilitation for What We Do

The problem with applying these models to audiology is that they assume total or near total correction. Few of us would disagree that the correction experienced by those fitted with eyeglasses or contact lenses is far different (more satisfactory?) from the results experienced by our patients fitted with hearing aids. And once orthodontic treatment is complete, the teeth and jaw have undergone a permanent change quite different (more satisfactory?) from the experience of hearing aid users.

Getting back to “rehabilitative audiology,” let’s consider two similar, yet significantly different, definitions of “rehabilitation>” The first, from the Merriam-Webster on-line dictionary, defines rehabilitation as “to bring (someone or something) back to a normal, healthy condition after an illness, injury, drug problem, etc.” Good definition, but somewhat problematic from an audiologic perspective, in that it is likely beyond our abilities to bring our patients back to a “normal, healthy condition” as most of the hearing problems we deal with are the result of irreversible physiologic damage with perceptual consequences that can’t be entirely resolved through the tools at our disposal (i.e., hearing aids).

Contrast this definition with the following from the on-line Free Dictionary: “to restore to good health or useful life, as through therapy and education.” This definition is similar to the first, but substantially different in the sense that the goal, as articulated in the latter definition, is not normalcy, but restoration to “good health or useful life” accomplished through therapy (i.e., hearing aids, auditory training, assistive technology, counseling, etc.) and education. This appears to be a goal that is quite achievable and is, after all, how we should be practicing our profession.

Hearing Loss as a Chronic Health Condition

These two definitions also seem to represent the dichotomy between the medical and the rehabilitative models of our profession. The first definition implies a cure/intervention (pharmaceutical, surgical or other therapy) that eradicates the disease or injury and returns the person to their pre-disease state. As I noted last month, this is a romantic and seductive perception of what we do but, in reality, we rarely “cure” anything or anybody. At our best, we help patients to manage a chronic condition (i.e., sensorineural hearing loss) “through therapy and education” (our second definition). So, let’s explore this concept of sensorineural hearing loss as a chronic health condition which, I believe, is a nice fit and can help to inform us how to better manage the consequences of end organ hearing loss.

Let’s compare, for example, diabetes (certainly a chronic condition) and sensorineural hearing loss. These are what the two conditions share in common, at least in their early stages. They are:

- invisible

- progressive

- painless

- incurable though manageable

- a challenge in terms of motivating patients to seek care

- a challenge in terms of compliance with treatment

- ‘front-loaded’ in terms of professional intervention

- most likely to be successfully treated through successful self-management

- most likely to be successfully treated through modifications in behavior as an adjunct to the primary intervention (medication for diabetes; hearing aids for hearing loss)

How Does This Help?

Assuming you buy into my argument, you might very well be asking yourself what we achieve by viewing hearing loss as a chronic health condition. Well, it turns out that in an effort to reduce the human and economic costs associated with such major chronic health conditions as heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure, the healthcare industry has, over the past several decades, embraced the concepts associated with chronic care management.

Assuming you buy into my argument, you might very well be asking yourself what we achieve by viewing hearing loss as a chronic health condition. Well, it turns out that in an effort to reduce the human and economic costs associated with such major chronic health conditions as heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure, the healthcare industry has, over the past several decades, embraced the concepts associated with chronic care management.

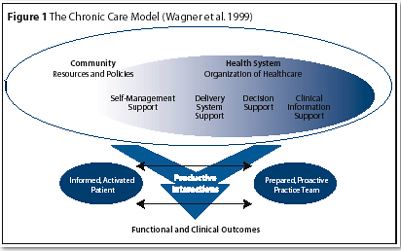

There is an impressive literature associated with chronic care management to include the development of The Chronic Care Model (CCM){{1}}[[1]]Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice. 1998;1(1):2-4.[[1]] (Figure 1). The CCM identifies six components critical for improving outcomes among patients with chronic health conditions:

- Self-Management Support

- Delivery System Design

- Decision Support

- Clinical Information Systems

- Organization of Health Care

- Community

Among these, self-management support offers important opportunities for optimizing the success of our patients with hearing loss and will be the subject of my next post.

This is Part 3 of the Peeling the Onion series. Click here for Part 4, Part 2 or Part 1.

Harvey Abrams, PhD, is currently Principal Research Audiologist at Starkey Technologies. Dr. Abrams has served in various clinical, research, and administrative capacities with Starkey, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense. Dr. Abrams received his master’s and doctoral degrees from the University of Florida. His research has focused on treatment efficacy and improved quality of life associated with audiologic intervention. He has authored and co-authored several recent papers and book chapters and frequently lectures on post-fitting audiologic rehabilitation, outcome measures, health-related quality of life, and evidence-based audiologic practice. Dr. Abrams can be reached at [email protected]

feature image by Ross Land/Getty