“There are no barriers [that discourage new entrants to the hearing aid industry]. New entrants simply have to comply with regulations intended to safeguard our patients.

This excerpt from a recent post on the PCAST report gives pause, prompting switching of hats from Audiologist to Economist. Though Hearing Economics has written on market barriers before, it hasn’t done an entire post on the topic. That oversight is corrected today as the occasional Econ 202 series is resuscitated again.

What’s a Barrier? Who’s an Incumbent?

A barrier is any resource cost faced by a wannabe that is not incurred by incumbents. In our case, incumbents come in two varieties:

- Big 6 hearing aid manufacturers and a few smaller firms classed as medical device manufacturers by the FDA

- Dispensers and audiologists licensed by states to fit hearing aids, usually by selling at retail

Barriers favor incumbents, thereby enabling inefficiencies in an otherwise competitive market. Inefficiencies can result in oligopolistic price manipulation — monopolistic or predatory — and restricted competition. Such inefficiencies introduce what economists charmingly call a “deadweight loss,” or a cost to society.

The name of the game for incumbents is to gain market power by making barriers formidable, perhaps impregnable — to the extent that incumbents succeed within and by the law, they can enjoy protection and profits not available in more competitive markets. If they succeed too well at blocking competitors and optimizing profitability, they invite market revolt, scrutiny by policy makers concerned about societal costs, and possible changes in the law.

Barrier or Sanctuary? Depends on the Vantage Point

The audiology quote that launched this post states that “comply(ing) with regulations intended to safeguard our patients” poses no market barrier. Or if it does, the implication is that it’s the only barrier and a simple one to boot. This is an understandable view for established audiologists to adopt since they are, after all, incumbents viewing the situation through a narrow, albeit licensed lens.

We may not have no stinkin’ barriers, but we sure got stinkin’ badges!

Viewed through the broader, badge-free economic lens, the no-barrier statement is simple and simply wrong. It glosses over all that goes into the making, distributing, and fitting of hearing aids as specialty medical devices in the regulated hearing market. Economics to the rescue!

Barriers to Entry (and Exit) in the US Hearing Market

Barriers are structural (e.g., rules and regs, infrastructure) and strategic (e.g., pricing, marketing, branding). The distinction isn’t important in today’s discussion, which is concerned solely with structural barriers brought about by regulation. But it will come up in discussion of other barriers in future posts.

Government Regulation, Federal and State

Manufacturers

FDA1 defines hearing aids as medical devices and exempts most (e.g., air-conduction) from “premarket review and clearance before marketing“:

“Hearing aid means any wearable instrument or device designed for, offered for the purpose of, or represented as aiding persons with or compensating for, impaired hearing.”2

Manufacturers pay the FDA a Device Facility User Fee prior to registering as a medical device maker or distributor. Thereafter, they must register annually and “list the devices and the activities performed on those devices at that establishment” in order to maintain incumbency. The regulations require specific labeling of and on all devices (e.g., device model, serial number, date of manufacture) and every device must be accompanied by a User Instructional Brochure provided by the manufacturer. 3

In and of themselves, the federal regulations for manufacturers do not pose a big barrier to entry or exit. Nevertheless, they add financial and recordkeeping costs to the process, which must be serviced annually as well as unit by unit.

Dispensers and Audiologists

FDA defines hearing aid dispensers and audiologists, respectively, as:

- Dispenser: “any person, partnership, corporation, or association engaged in the sale, lease, or rental of hearing aids to any member of the consuming public …”4

- Audiologist: “any person qualified by training and experience to specialize in the evaluation and rehabilitation of individuals whose communication disorders center in whole or in part in the hearing function.”5

No fees attach to those definitions, but recording and recordkeeping requirements in the 1977 Final Rule add small but persistent financial and time costs to the dispensing process on a unit by unit basis. In 1997, the FDA self-initiated a year-long study aimed at reducing the record keeping and reporting burdens without deleteriously affecting consumer/patient care.

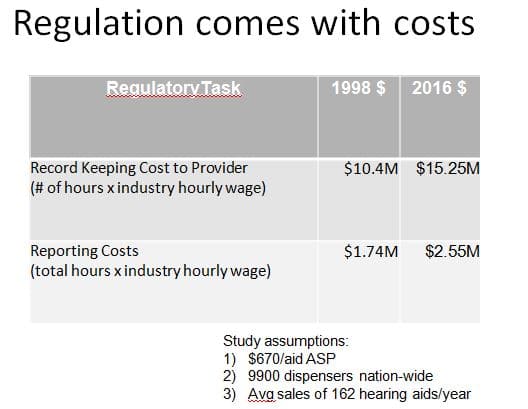

The FDA’s report (covered in a previous post series) went to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in 1998. The calculated regulatory reporting burden at retail (Table 1) netted out to about $11/aid in today’s dollars. Not much, but still a systematic cost that raises the market barrier a bit and is likely higher today due to HIPAA regulations and insurance reporting requirements.

Table 1. 1998 FDA report to the OMB on reporting and recordkeeping costs of hearing aid dispensing, using estimates of dispensing statistics from that year.

The FDA definition of an audiologist specifies qualifications of training and experience, but does not stipulate further. That has been accomplished in state audiology licensure laws that require audiology applicants to scale barriers of varying height and cost:

- possess specialized education (Masters or Doctorate) from an accredited program (this is a significant cost in time and money)

- pass a national praxis examination

- pass a state examination

- pass a criminal background check

- pay an application fee

FDA is mute on training and experience requirements for dispensers, but state license applicants generally must check off items #3-5 on the list above.

Further, states require audiologists and dispensers to regularly renew licenses, pay a renewal fee, and obtain CEUs to maintain incumbency. Some CEUs may be”free,” but none come without substantial allocation of time, which adds another cost.

Finally, federal and state regulations are not always in accord on specifications and definitions, which contributes a few bricks of confusion to the barrier. Barriers vary state by state unless challenged under federal law. Legal confusion and costly litigation can and have arisen regarding required/optional services (e.g., hearing test), distribution channels (e.g., mail and Internet, Big Box), and even the legality of states requiring a license to “fit and dispense” hearing aids.

One Hurdle Jumped, Lots More to Go

Overall, regulatory burdens for manufacturers or licensed retailers exist but they’re not showstoppers. Manufacturers of ear devices tell me it’s “not a big deal” to qualify as a medical device manufacturer. Perhaps that’s in part because they are already fabricating ear level devices, almost incumbents.

Professionals reading through this first barrier are likely to shrug it away as either a sunk cost (e.g., education) or something so ubiquitous that we take it for granted (e.g., annual renewal and CEUs). We also appreciate that it prevents unqualified people from intruding on our livelihood and, perhaps, adversely affecting the hearing health of consumers. I do not think there is data to support that second assumption, but welcome receiving some from more informed readers.

Walls are built brick by brick; stations along an obstacle course pose different degrees of challenge. Ditto for economic barriers for hearing health care.

Walls are built brick by brick; stations along an obstacle course pose different degrees of challenge. Ditto for economic barriers for hearing health care.

Next post looks at other barriers in manufacturing or retail delivery of hearing aids, including:

- Start Up Costs

- Technology

- Economies of Scale

- Product Differentiation

- Access to Suppliers and Distribution Channels

- Competitive Response

References

- The CDRH, a branch of the FDA has oversight: “The Center for Devices and Radiological Health is responsible for the premarket approval of all medical devices, as well as overseeing the manufacturing, performance and safety of these devices.”

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 — Food and Drugs. Chapter I — Food and Drug Administration Department o Health and Human Services. Subchapter H — Medical Devices. Part 874 — Ear, Nose and Throat Devices. Subpart D – Prosthetic Devices. Section 874.3300 — Hearing Aids.

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 — Food and Drugs. Chapter I — Food and Drug Administration Department o Health and Human Services. Subchapter H — Medical Devices. Section 801-420 (b.1) Hearing Aid Devices; professional and patient labeling. Label Requirements for Hearing Aids.

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 — Food and Drugs. Chapter I — Food and Drug Administration Department o Health and Human Services. Subchapter H — Medical Devices. Section 801-421 (c.2) Hearing aid devices; conditions for sale.

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 — Food and Drugs. Chapter I — Food and Drug Administration Department o Health and Human Services. Subchapter H — Medical Devices. Section 801-420 (3) — Hearing Aid Devices; professional and patient labeling. Dispenser.

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 — Food and Drugs. Chapter I — Food and Drug Administration Department o Health and Human Services. Subchapter H — Medical Devices. Section 801-420 (4) — Hearing Aid Devices; professional and patient labeling. Audiologist.

This is Part 1 of a 5-part series on barriers. Click for Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, or Part 5.

Feature image from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre obstacle image from Craig Cherlet