Eugene Worth, MD

I find it amazing to come into contact with the most interesting persons in the most unusual places. This was the case with Gene Worth, who was just another face in the softball league that I play in. However, during casual conversations, I found out that he had a very special background and very interesting work activities.

Dr. Eugene Worth is the Medical Director for Hyperbaric Medicine at Dixie Regional Medical Center in St George, Utah. Dr. Worth received his MD degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, in Columbia Missouri. He then completed his internship and residency in Anesthesiology at the University of Missouri-Columbia Hospital and Clinics. Dr. Worth is a board-certified Anesthesiologist with 13+ years in private and academic practices. His sub-specialty area was cardiac and major vascular anesthesia including heart transplantation. He has received many honors and awards for his work, and he is a prolific researcher and author. He has practiced wound care and hyperbaric medicine since 2002. The latter is of special interest because this sub-specialty, where he is certified in Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine, often leads him to engage in underwater research. And, much of what he sees and treats relates to middle ear and Eustachian tube disorders. He is a recreational diver and a NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Diving Medical Officer.

–Wayne Staab, PhD, Editor

by Eugene Worth, MD

Underwater sports, including a variety of diving activities, are common. For as long as there have been humans and water, freediving (also known as breath-hold diving) has been present. The longer one can hold a breath, the more activity can occur under the surface of the water. SCUBA is relatively new to the scene of underwater activities.

There have been attempts to provide surface air to the diver under the water since the early 1800s. Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus (SCUBA) has gained popularity outside of the industrial or military applications since the time of Jacques Cousteau.

Exploring Common Pathology of the Ear and Sinuses

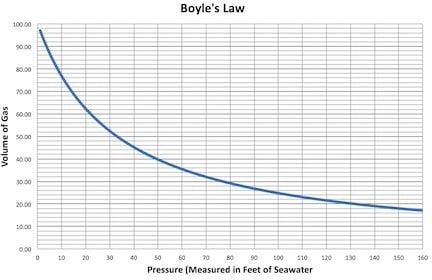

Without writing a textbook on the subject, we will explore some common pathology of the ear and sinuses. Most of the pathology depends on application of simple gas laws. For example, Boyle’s law (Figure 1) states that by keeping temperature constant, a volume of gas is related inversely to the pressure applied to it (Sound somewhat familiar to those of us looking at the effects of reduced ear canal volumes and SPL increases?).

For example, a balloon containing 1 liter of gas at 1 atmosphere of pressure is now subject to 2 atmospheres of pressure. The resulting volume of that balloon is now 1/2 liters. The density of the gas has changed, as well as the volume.

Figure 1. Boyle’s law states that by keeping temperature constant, a volume of gas is related inversely to the pressure applied to it.

Middle Ear Cavity and Boyle’s Law

Let’s apply this information to the middle ear cavity. If the volume of the middle ear cavity does not accommodate an incremental change in pressure, then at 2 atmospheres of pressure, we would expect the volume of the middle ear cavity to be half the size it was when we started. That is the principle behind the pathology of middle ear barotrauma. Without being able to equalize pressure in the middle ear through auto-inflation of the Eustachian tube, then the volume of the middle ear decreases with increasing pressure caused by exposure of the body to increasing depth in the ocean. This results in pain, bleeding in the tympanic membrane, blood or exudate in the middle ear, and finally, tympanic membrane rupture.

Successful SCUBA Divers

A successful SCUBA diver must be able to control the Eustachian tube and equalize the pressure between the middle and external ear at will. While this sounds simple, many divers have problems with middle ear equalization.

Barotrauma is the most common diving injury. The tympanic membrane can rupture with as little as 4 feet seawater change in pressure (100 mmHg). Of course, there is a story that illustrates many of these problems. Middle ear barotrauma is a problem that almost always occurs in the descent (or pressurization) phase of a SCUBA dive. It rarely happens on ascent (depressurization). Barotrauma may be referred to in a slang form by some divers, calling it a “squeeze.”

“Achieving middle ear equalization is a fundamental skill for SCUBA divers, as barotrauma, often referred to as a ‘squeeze,’ can lead to injuries like tympanic membrane rupture even with minor pressure changes. Successful equalization is crucial for a safe diving experience.”

Illustrative Story

I was to spend an idyllic week with a “group” of divers on the island of Bonaire*. Due to unforeseen problems, only 4 people went on the trip. Of these 4, only 3 were divers. All of the divers had “Advanced Open Water” certification. This generally means having at least 50 dives total with some expertise in buoyancy, underwater navigation, and other learned skills beyond introductory courses.

After checking our equipment, adding weights for buoyancy control, and pre-dive briefing, we dropped into the ocean and started our descent. I’m lucky enough to be able to easily control my Eustachian tubes. After several breaths and minimal effort, I was at 33 feet of seawater pressure. I checked my buoyancy and was floating just above the reef. Hmmm … all alone in the world. Turning over on my back and looking up, I saw the husband/wife pair at 10 feet of seawater, both of them pointing to an ear. This signal means, “I’m having trouble clearing.” Then came the OK sign, which means to carry on, “I’m doing OK.”

A brief break in the story for some SCUBA physics. We speak of ‘feet of seawater’ as though it is a depth. That is true, however, feet of seawater is also a pressure. One atmosphere of pressure is equal to 33 feet of seawater or 34 feet of freshwater. At sea level, this is equivalent to 14.7 pounds per square inch or 760 mmHg, if measured on a standardized pressure gauge.

In terms of our SCUBA dive, it meant that I was using valuable air while floating at depth when we could have been exploring the reef. After 20 minutes (about half of the total dive time), they were able to join me at depth.

By the third day of the trip, this routine was getting old. I would stay on the surface and snorkel while they worked at ear clearing and slowly made depth. Then, I would join them when they were on the bottom. After our second dive of the day, the wife said, “My ear finally cleared! I felt a pop and fizzle of air come out of my ear.” This is not the type of thing a diving medicine physician wants to hear. It almost always means that the tympanic membrane has ruptured. This introduces the potential for saltwater contamination of the middle ear, frequently resulting in dysequilibrium and an otitis media. After exiting the water from that dive, we made a trip to one of the local physicians. He has been a friend for many years and quickly looked at her ear. After examination, we both decided that this was a small perforation that was not grossly visible. To be safe, she needed to stay out of the water for several days.

Middle Ear and Sinus Barotrauma

Middle ear barotrauma is common and can ruin a perfectly good diving vacation. The ears are not the only parts of the body affected by pressure and Boyle’s Law. There can be sinus pain if the opening to the sinus is small, swollen, or otherwise affected. Sinus barotrauma depends totally on the size of the sinus ostia and very few techniques can be used to avoid it. Repetitive episodes of sinus barotrauma may lead to other complications. We will discuss one of those in a future column.

*Bonaire is a special municipality within the country of the Netherlands. It is one of the three BES islands located in the Caribbean Sea, the other two being Sint Eustatius and Saba. It is located less than a hundred miles off the north coast of South America near the western part of Venezuela.

**this piece has been updated for clarity. It originally published on August 2, 2016