The Hearing Disruptions series seeks to cover the rapid changes taking place in hearing healthcare. Today’s post is culled from recent topics presented to the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) Committee on Accessible and Affordable Hearing Health Care for Adults.

A Bi-Model Market for Hearing Aids and Ear Amplifiers

Holly Hosford-Dunn, Ph.D. Presented at the June 30 IOM meeting regarding hearing aid availability (click here for part 1 and part 2).

The hearing device market is bimodal and not in equilibrium, meaning that it is not functioning efficiently for suppliers or consumers. A hearing aid report card by Dianne van Tasell, PhD,1 scored hearing aids high on effectiveness (based on verification and validation studies) but low on price and access (Fig 1).

As Van Tasell pointed out to the IOM Committee, federal and state regulations restrict access to a Supply line comprised only of devices approved as hearing aids (Fig 1, middle column).

- Those devices are only manufactured by a handful of specialty high tech companies that can afford the approval process.

- All or almost all such devices are only dispensed by practitioners who’ve met and met the requirements and paid for the right to obtain specialty state licensure, and who dispense out of expensive bricks and mortar environments.

Pricing Strategies Shaped by Demand and Public Policy

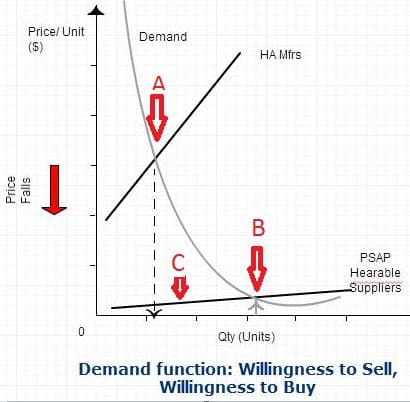

Monopolistic pricing is the strategy of choice at each stage in the restricted hearing aid Supply function (Fig 2). That places hearing aids predictably on the economic demand function — high, inelastic Price; low Quantity demanded (point A in Fig 2). In other words, like other healthcare, hearing aid care by approved methods is rationed by price and access.

Figure 2. Representative Demand function for ear level devices in today’s market, showing different price points for hearing aids (A), PSAP/Hearables (B), and lower quantity demanded for PSAP/Hearables than available supply (C).

“Ration,” which probably stems from Latin “ratio” and relates to “rational,” is a much abused and confused word in our language. Though guaranteed to raise ire, it deserves thoughtful definition by two distinct, often divergent, paths in the present discussion.

- Economically defined, healthcare rationing is simply limiting health care goods and services to only those who can afford to pay. In the United States this type of rationing affects about 15% of the population, who are either too poor to afford care or unwilling to buy care or simply uninsured.

- Defined by regulatory means, healthcare rationing involves restricting health care goods and services from even those who can afford to pay. In the United States this type of rationing affects anyone in need of licensed healthcare services, prescription medications, and FDA regulated products, such as Class I and Class II hearing devices.

By contrast, the FDA-delimited Wellness Model of PSAPs and Hearables makes them directly accessible at low prices giving them high scores in those categories (Fig 1, right column). Ear amplifiers don’t get a grade for effectiveness because the data is lacking, although a few small studies suggest they could be comparable to hearing aids. Yet, even with regulation-free products and a Supply line of many suppliers willing to sell at a very low prices, consumers’ willingness to purchase is well below available (or potential) product production (points C and B in Fig 2, respectively).

The Misbehaving Market

The market conditions depicted in Figures 1 and 2 say several things:

- Most consumers are expressing their preference to live with hearing difficulty rather than adopting an ear level device of any kind.

- Barriers other than Price are holding back the market: regulatory restrictions on the high end and incomplete consumer information on the low end of Price.

The “misbehaving” market poses a considerable and continuing challenge for the device industries. Further, emerging research is making it increasing evident that the market reflects potential ongoing and undesirable health situations for those with hearing difficulty. This may be especially so for those who could benefit from amplification regardless of how it’s defined.

Market forces resist barriers of regulation, turf, and definition as they push the market toward equilibrium. Part 4 of this presentation considers three such forces and their predicted effects on market behaviors.

References

1Van Tasell D. Hearing aids, enabling technologies, barriers. IOM Committee on Accessible and Affordable Hearing Health Care for Adults. April 27, 2015.

Sources

- Amlani AM & De Silva DG. Effects of economy and FDA intervention on the hearing aid industry. Am J Aud. 2005;14, 71-79.

- Consumer Electronics Association. 2014 CEA Personal Sound Amplification Products (PSAPs) Study.

- Hosford-Dunn, H. If hearing aids were hula hoops. HearingHealthMatters.org, June 17, 2017.

- Hunn N. The market for smart wearable technology: A consumer centric approach. 8/07/2014

- Lin FR et al. Hearing Loss and Incident Dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):214-220. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.362.

- Lin FR et al.Hearing Loss and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):293-299. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868.

feature image courtesy of eugenio pirri

for the people facing hearing losses hearing aids r the best because with the help of this tiny device they can live their life just like normal people and spend a very healthy life, other ways such as surgery are very dangerous and can cause many other problems

http://claimhearinglosses.co.uk/

Unfortunately, hearing aid professionals on both sides of the fence practice “rent-seeking behavior” through the process of “regulatory capture.” As I explained in November 2012 in the comments here:

https://hearinghealthmatters.org/hearingnewswatch/2012/blogger-gets-ahead-of-the-pack-on-news-of-made-for-iphone-hearing-aids-coming-your-way-soon/

1) Rent-Seeking Behaviour:

“Rent seeking” is one of the most important insights in the last fifty years of economics and, unfortunately, one of the most inappropriately labeled. Gordon Tullock originated the idea in 1967, and Anne Krueger introduced the label in 1974. The idea is simple but powerful. People are said to seek rents when they try to obtain benefits for themselves through the political arena. They typically do so by getting a subsidy for a good they produce or for being in a particular class of people, by getting a tariff on a good they produce, or by getting a special regulation that hampers their competitors. Elderly people, for example, often seek higher Social Security payments; steel producers often seek restrictions on imports of steel; and licensed electricians and doctors often lobby to keep regulations in place that restrict competition from unlicensed electricians or doctors.

But why do economists use the term “rent?” Unfortunately, there is no good reason. David Ricardo introduced the term “rent” in economics. It means the payment to a factor of production in excess of what is required to keep that factor in its present use. So, for example, if I am paid $150,000 in my current job but I would stay in that job for any salary over $130,000, I am making $20,000 in rent. What is wrong with rent seeking? Absolutely nothing. I would be rent seeking if I asked for a raise. My employer would then be free to decide if my services are worth it. Even though I am seeking rents by asking for a raise, this is not what economists mean by “rent seeking.” They use the term to describe people’s lobbying of government to give them special privileges. A much better term is “privilege seeking.”

It has been known for centuries that people lobby the government for privileges. Tullock’s insight was that expenditures on lobbying for privileges are costly and that these expenditures, therefore, dissipate some of the gains to the beneficiaries and cause inefficiency. If, for example, a steel firm spends one million dollars lobbying and advertising for restrictions on steel imports, whatever money it gains by succeeding, presumably more than one million, is not a net gain. From this gain must be subtracted the one-million-dollar cost of seeking the restrictions. Although such an expenditure is rational from the narrow viewpoint of the firm that spends it, it represents a use of real resources to get a transfer from others and is therefore a pure loss to the economy as a whole.

http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/RentSeeking.html

2) Regulatory Capture:

Regulatory capture is a theory associated with George Stigler, a Nobel laureate economist. It is the process by which regulatory agencies eventually come to be dominated by the very industries they were charged with regulating. Regulatory capture happens when a regulatory agency, formed to act in the public’s interest, eventually acts in ways that benefit the industry it is supposed to be regulating, rather than the public.

Investopedia explains “Regulatory Capture”

Public interest agencies that come to be controlled by the industry they were charged with regulating are known as captured agencies. Regulatory capture is an example of gamekeeper turns poacher; in other words, the interests the agency set out to protect are ignored in favor of the regulated industry’s interests.

http://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/regulatory-capture.asp

Captured Agency:

A government agency, especially a regulatory agency, that is largely under the influence of the economic interest group(s) most directly and massively affected by its decisions and policies — typically business firms (and sometimes professional associations, labor unions, or other special interest groups) from the industry or economic sector being regulated. A captured agency shapes its regulations and policies primarily to benefit these favored client groups at the expense of less organized and often less influential groups (such as consumers) rather than designs them in accordance with some broader or more inclusive conception of the public interest.

http://www.auburn.edu/~johnspm/gloss/captured_agency

Hi Dan — next time you decide to write like this, I hope you’ll send it to me so we can put it up as an Econ 202 post. I hate to see useful information like this buried in the Comments section.

But, hey — what’s wrong with the word “rent?” I kind of like it. Just because you pay to play and get a favorable treatment (e.g., subsidy) doesn’t mean you own the mortgage. You’re just benefiting by renting the favorable treatment till some one else comes along and pays more rent. Thanks, Holly