I recall meeting Margaret (Margo) Skinner at a conference back in the early 1980s and, other than being struck by how nice she was, Margo commented that she had really only published 2 or 3 articles at that time, yet she was already considered a world authority.

Margo Skinner (circa 1980s)

Well, that was my view- she would have never considered herself a world authority, but I would. What was it about her research that struck such a chord, and in today’s jargon, had gone viral?

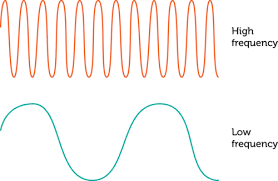

The publication with J.D. Miller in 1983 was about Margo’s PhD thesis. Despite being almost 40 years old, this article is a must-read. Margo Skinner used a master hearing aid where she was able to increase the high frequency gain and output or the low frequency gain and output, independently of each other.

One of her most important findings was that in order to optimize intelligibility (and sound quality) for each increase in the high frequency region of amplification, one also required a corresponding low frequency increase as well. Just increasing the higher frequency amplification alone resulted in less-than-optimal intelligibility (and a “tinny” sound quality).

This has been known clinically for years- whenever there is a clinical modification to increase the higher frequency sound transmission, whether acoustically (e.g., Libby horn) or electronically, one needs to increase the bass response as well in order for the client to be more accepting the sound quality.

Her findings have special importance for today where hearing aids have an extended high frequency capability. Hearing aids of the 1980s only extended up to 4000 Hz and it was rare to be able to significantly extend that upper limit, however modern hearing aids can now extend beyond 6000 Hz, and in some cases above 8000 Hz.

Should there therefore be a low frequency extension to balance with this new found high frequency transmission of sound? And while the answer to this question would apply equally to speech as it does to music, we will start off with music as an input to a hearing aid.

Should there therefore be a low frequency extension to balance with this new found high frequency transmission of sound? And while the answer to this question would apply equally to speech as it does to music, we will start off with music as an input to a hearing aid.

Music and an extended bandwidth in Hearing Aids

Some of the music programs that are currently implemented in modern hearing aid technology seek to increase the bandwidth, especially in the higher frequency region over the program(s) for speech. This is erroneous on two counts:

- There is no research data suggesting that amplified music should have a different frequency response than amplified speech, and

- Based on Skinner and Miller (1983) it is possible that a high frequency increase alone will be less than optimal unless there is an “equivalent” low frequency increase as well.

If a hard of hearing client can tolerate an increased bandwidth in the higher frequency region, this increase should be implemented for all programs- speech and music. It is true that much of the research on extending the upper limit of the frequency response has been performed with music in mind, but this should be applicable to all hearing programs, albeit for slightly different reasons.

A high frequency extension for music would increase the “fullness” and “clarity” of music, but for speech, there would be an increase in the ability to discern spatial cues. (Moore and Tan, 2003).

The research is also clear, at least for music, that an extended low frequency cut-off (down to 55 Hz) of the frequency response can be beneficial for music, but this derives from well-controlled laboratory studies (e.g., Moore and Tan, 2003). Of course, this is frequently accomplished clinically with non-occluding ear-tips where unamplified low frequency sound is allowed to enter the ear canal directly, by-passing the hearing aid, despite the electronic specification of the hearing aid having a 200 or 250 Hz low frequency cut-off. Fortunately, with the advent of feedback management control algorithms, we are able to fit hearing aids with larger vents, and in many cases, would be completely non-occluding earmold configurations. And if this is allowed for music, according to the results of Skinner and Miller (1983) it is hypothesized that there should be an associated high frequency boost as well.

However, if there are cochlear dead regions that limit the high frequency end of the frequency response (such as with hearing losses greater than a moderate level (Moore and Tan, 2003) or with steeply sloping hearing losses (Ricketts et al., 2008)), then caution should be exercised with using a non-occluding ear-tip/earmold coupling system that would allow an extended low frequency cut-off of the hearing aid frequency response. A narrower frequency response (on both ends) may be better than the “theoretical” wider frequency response.

References:

Moore, B.C.J., and Tan, C-T. (2003). Perceived naturalness of spectrally distorted speech and music. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 114, 1, 408-419.

Ricketts, T.A., Dittberner, A.B., and Johnson, E.E. (2008). High frequency amplification and sound quality in listeners with normal through moderate hearing loss. Journal of Speech-Language-Hearing Research. 51, 160–172.

Skinner, M.W., and Miller, J.D. (1983) Amplification Bandwidth and Intelligibility of Speech in Quiet and Noise for Listeners with Sensorineural Hearing Loss, Audiology, 22, 3, 253-279.