We’ve graduated from Econ 101. It’s time to take on Price Takers — companies that can influence Price to optimize their profits. That’s going to take a few posts, starting with a rehash of Econ 101 posts today. Apologies to those who don’t like going into the weeds, but you really can’t talk about economic pricing without knowing the underlying theories and models.

Econ 101 Review

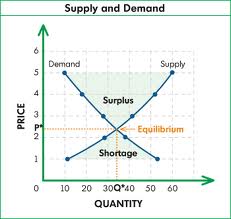

So far, the economic discussion has stayed in the nice, albeit imaginary, world of free markets shown in Fig 1.

- Consumers and supplier make rational choices insofar as their respective Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Supply.

- The choices are rational because consumers are privy to all information, which means no Supplier has a competitive edge and all consumers optimize their Utility within their individual budgets.

- Demand Curves are downward sloping, left to right: more Quantity Demanded (Qd) as Price (P) decreases.

- Supply Curves are upward sloping, left to right: more Quantity Supplied (Qs) as Price (P) increases.

- Inevitably, the two curves intersect and this is the point where the market sets the Equilibrium Price (P*) and Equilibrium Quantity (Q*), as shown in Fig 1.

- Economists say the Market Clears at Equilibrium: Suppliers produce as much as they can without losing money and Consumers pay according to their Utility and budget constraints, ceteris paribus (econ speak for “all other things held constant” and Latin for “others things being equal.”)

- Like a thermostat, the market fluctuates around Equilibrium: when Prices go up, suppliers produce more but find too few buyers (Surplus in Fig 1). When prices go down, suppliers produce less than buyers want (Shortage in Fig 1). In both cases, Supply and Demand adjust and Equilibrium is restored.

- The only way to effect a change in P* is for the Market to change its point of Equilibrium. That only happens when Supply side shocks (e.g., technological innovation) or Goods Market shocks (e.g., improved global economy) shift the Supply and Demand curves.

How Do Audiologists Fit Into The Imaginary Free Market?

The take home from Econ 101 is that the market sets P*, not you, me, or any other independent Audiologists. That’s the position I’ve taken in past posts and I’ll stick with it for now, though it’s a bit of a gloss over and we’ll get to that later.

For now, suffice it to say that independent Audiologists lack sufficient clout to influence the overall market. As Price Takers, we are compelled by market forces to set our individual P pretty close to P* if we plan to survive.{{1}}[[1]]Of course, we can always fiddle around with bundling and unbundling to change the appearance of Price, but in the long run, all aspects of our goods and services need to conform fairly closely to Market prices for those commodities and services.[[1]]In other words, we do not have a downward sloping Demand curve like the over all market. Ours is a boring, flat Demand “curve” dictated by market forces outside our control.

Visually, Fig 2 says it all{{2}}[[2]]Fig 2 courtesy of Pennsylvania State University.[[2]]. For an individual firm (you or me), the Demand Curve flatlines at P*, which means that our marginal revenue (MR) is exactly the same for every additional good or service we produce/sell: we make P* for every unit we produce, no more, no less.

Past posts and common sense tell us that we have to stop producing when our marginal costs (MC) get bigger than MR. If it costs us more to produce a unit than we make from that unit, we are in trouble. This makes it pretty simple: we want to produce right up until MC =P* , which coincidentally = MR = D.

Talk about the old Invisible Hand! There’s no Free Will in the Free Market. If we set our Price above P*, the market will look elsewhere and we’ll eventually go out of business. If we set our Price below P*, our costs will exceed our revenues and we’ll go out of business as well. This is why I’m always harping on cost cutting measures — it’s the only margin over which we can exercise any control and gain a competitive advantage.

Those Crafty Price Makers

Not everyone is constrained by P*. Price Makers have the luxury of setting their own P, typically higher than P*, without going out of business. In fact, that’s the business they’re in — to optimize profits (so-called “abnormal” profits in econo-speak) by playing around with P.

The simplest theoretical example of a Price Maker is a Monopoly — an industry in which there is only one firm selling the product. We do not have any Monopolies in our industry, but it’s convenient to use the Monopoly Model to illustrate the basic economic theory underlying price setting behaviors of Price Makers. We’ll do that in the next post, then move on to Oligopolies and Cartels, of which we have several.