by Kate Baldocchi, AuD, Trisha Milnes, AuD, & Amyn M. Amlani, PhD

COVID-19 proved to be a curve ball that left governments, economies, healthcare systems, and the citizens of the world in dismay. The impact of the virus tested our emotional-, mental-, familial-, social-, and physical-wellbeing, as well as our resilience, our grit, our humanity, and our adaptability. As societies recover from the effects of the pandemic, many traditional sectors—such as education, healthcare, and front-line worker supply—will be seeking to improve the manner in which they operate and provide services in the future through design thinking.

In the hearing care space, COVID-19 markedly impacted the ability of impaired listeners to receive diagnostic and treatment services. In the best case, hearing aid owners were able to receive modified services through the creativeness of the provider. The ability to supply diagnostic services to listeners, however, proved to be an epic challenge on a global scale. As one might expect, the supply channels that once allowed providers to reap financial benefit had essentially come to a halt, and this lack of patient flow and conversion left many businesses in an economic quandary. The virus also forced many providers to embrace service delivery technologies—such as video conferencing for patient consultations and using remote capabilities to adjust hearing aids—that they may not otherwise have taken on. These challenges, we believe, will redefine the methods in which hearing care is delivered moving forward.

As we look to the future, the recent experiences have shed light on the critical need for refined diagnostic and treatment protocols. As these protocols are created and tested, the objective should be to utilize iterative steps to ensure the service delivery assumptions, and the alternative strategies and solutions, are synergized to include the needs and values of the provider and the user. Successful achievement of this objective, therefore, must consider implementing design thinking—a solutions-based approach to problem solving.

Design-Thinking Revisited

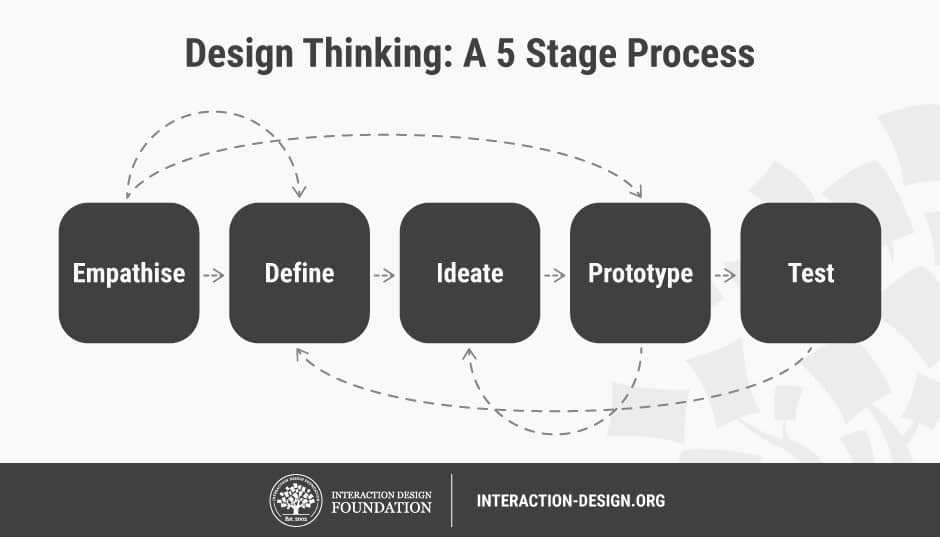

Design thinking was introduced in a 2019 HHTM blog as a potential tool to evaluate and re-evaluate access and barriers in the hearing care space. Recall, that design thinking is predicated on a non-linear workflow that involves working through a 5-stage process.1

In this blog, our focus is to provide the reader with the basic tenets of the Empathize phase, where the primary goal is to understand the thoughts, values, hardships, and priorities of the listeners that we serve. Empathy is the basis of caring and sharing attitudes in the patient-centered care (PCC) model, where providers view the patient as a whole person, rather than simply treating the problem or disorder.2 For clarity, empathy is defined as:

“The ability and willingness to recognize and understand the thoughts, emotions, motives, and personality traits of another person.”

-Michael Lewrick, Patrick Link, Larry Leifer, The Design Thinking Playbook

Hearing Healthcare Providers and Empathy

As hearing health continues to evolve from a medical model to a PCC model, barriers to treatment remain pervasive. Historically, access and affordability have been discussed as limits to increasing market penetration. Recent findings, however, indicate that the provider’s behavior negatively influences patient readiness and, subsequently, compliance to provider recommendations for treatment.3

As an example, the research findings reveal that subjects’ pre-disposed expectation towards hearing care (i.e., measured two weeks prior to hearing evaluation in a rehabilitative setting) yielded an empathy score of 8.67 (out of a possible score of 10). The same outcome was measured post-visit (i.e., within two weeks of complete hearing evaluation) with the same subjects reporting a mean provider empathy of only 3.66 (out of a possible score of 10).

While the findings reported in the Amlani study3 are alarming, one must also realize that data was collected prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. In our “new” world, one could only assume that listener expectations to empathy have increased. The question is: “have providers narrowed the gap between listeners’ expectations and what they can provide?” The answer to this question will dictate, at a minimum, the degree of influx that new, and many aided, listeners seek hearing care.

So, Then, What is the Disconnect?

One possible rationale for the lack of empathy shown by the provider could stem from cognitive bias. Specifically, the Dunning-Kruger Effect (DKE), asserts that people have a gap in their knowledge, and this gap exposes their lack of awareness. To generalize this phenomenon, hearing care providers are often disillusioned that they are familiar with the lifestyle (i.e., values, needs, wants) and experiences of listeners with hearing loss simply because they have the education to diagnose and treat the disorder.

Using Design Thinking in the Empathize Phase

Design thinking is not about surveys and statistics.

“Data surveys are great for the what but not so great for understanding why.”

“When all you have are statistics, you have to guess what your customers are thinking.”

Instead, the empathizing phase should utilize techniques from ethnography fieldwork, an observational, qualitative research approach. Ethnography defines social anthropology and ethnographers gather insights on a specific culture by immersing themselves with the people they are studying over a long period of time.

Activities in the design thinking empathize phase include interviews and observation of people in their own environments; essentially, engaging with hearing health patients outside of the sound booth.

Below are the steps recommended when considering the Empathize phase:

1) Reframing Unlocks Innovation: Questions are the foundation of the Empathize phase, where inquiry and creativity are the fountainhead of innovative solutions. Shifting to an inquisitive mindset, how we frame the questions we ask, and who we ask questions of can keep the biases (i.e., DKE) and assumptions that limit our perspectives to a problem in check.

2) Build a Team: Whether design thinking is applied at the level of small business or scaled to the needs of a large company, the methodology starts with assembling a team. Establishing a team with diversity of thought and life experiences can ensure a more unique and successful human-centered solution. As noted above, an individual’s empathy towards others will always be observed through the biased lens shaped by his own personal experiences. Authentically including patients that you serve on your design team will assist with problem identification accuracy and uncover positive deviance in your target audience.

This can be accomplished by stacking your team with members of your target audience and cross-disciplinary participants.4-6 The value of including hearing health listeners to service delivery and product design in our industry cannot be overstated. The outcome for companies who choose to “design with disability” will be revolutionary. As an example, Elise Roy, deaf polymath and Accessibility and Inclusion Lead at Google, shares the importance of “sideways” perspectives that people with disabilities can bring to product and service design in her TED Talk.

3) Frame the Challenge: With your team assembled, collectively decide on an initial definition of the problem. Iteration is key to design thinking across all phases, and this includes identifying the problem, and re-identifying the problem. Discuss what the team knows about the topic and what they do not, research competitive products and services.4 Part of a human-centered design approach allows for the problem to be reframed based on the insights gathered from the interviews.

4) Interview People & Interview Experts: Select interviewees from your target audience and experts in the industry. Learn from both mainstream and extreme people in your target audience. What insights would a person with moderate high-frequency hearing loss (target – mainstream), a couple who are both implant recipients (target – extreme), or a psychologist specializing in hearing health (expert) expose?

Traditionally, empathy interviews are conducted in the home or workplace of the interviewee. In the current climate, ask the people you are interviewing their preference of video conferencing service and make sure you are comfortable navigating this service prior to your meeting. Most likely, your interviewee will enlighten you on accessibility features (such as Live Captions on Google Meet).

To get the most out of the time with the people you interview, prepare by:

- Listing general and specific questions: (see Appendix A)

- Arranging tools to take notes: to document interviewee quotes and your “a-ha!” moments

- Embracing a curious mindset: to eliminate judgmental thoughts and keep assumptions in check.7

Along with positive insights from interviews, be prepared for answers that may not agree with the standard quo. Embracing, and acting on these challenging insights can set you apart from your competition. If these challenges were easy, they would have already been resolved.

5) Observation by Immersion: When you see a person in public wearing hearing aids, what are your first thoughts? Many providers lean towards, “What is the hearing aid manufacturer?” or “How old are those devices?” Now ask yourself, do these questions positively shape the behavior of listeners towards provider recommendations and acceptance of amplification?

When designers observe, they ask themselves, “What is this person seeing, hearing, saying, doing, thinking and feeling?” “What is their body language conveying?” The questions asked by designers allow for a different engagement with the target audience.

Lastly, observing people in public offers rich opportunities to witness familiar situations with “fresh eyes.” For remote options, you can still ask designer observation questions by conducting secondary research and learning from hearing loss advocates.

In Summary

Businesses that understand and act on their consumers’ needs identified through design thinking methodologies realize the intrinsic and extrinsic values human-centered design can deliver. Case-and-point: as we navigate in what will become our new “normal” for servicing impaired listeners, design thinking offers opportunities to improve PCC not only for in-person care, but also in the lesser known, impending virtual environment.

As a profession and industry, we have an opportunity to re-shape hearing care while reducing barriers. Our future success with this opportunity is dependent on assuring that all perspectives are considered, and design thinking offers us a tool to achieve that perspective. In a future segment, we will continue with the next phase of design thinking called Define.

References:

- Dam RF, Teo YS. (2020). 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process. Interaction Design Foundation.

- Mudiyanse RM. (2016). Empathy for Patient Centeredness and Patient Empowerment. Journal of General Practice, 4(1). doi:10.4172/2329-9126.1000224

- Amlani AM. (in press). Influence of provider interaction on patient’s need recognition towards audiological services and technology. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology.

- Acumen Academy + IDEOorg. Introduction to Human-Centered Design.

- West F. (2018). Authentic Inclusion: Drives Disruptive Innovation. Frances West, USA.

- Knapp J, Zeratsky J, Kowitz, B. (2016). Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days. Simon & Schuster: New York, New York. https://www.gv.com/sprint/

- Bregman, P. (2020). Empathy Starts with Curiosity. The Harvard Business Review.

About the Authors

Kate Baldocchi, AuD, is sales professional, designer and audiologist in Austin, TX. Dr. Baldocchi is a proponent of human-centered design in hearing healthcare, who envisions design as a vehicle for innovation that can help improve the lives of impaired listeners and the approaches providers utilize in service provision.

Trisha Milnes, AuD, CCC-A, AIB-VAM is Chief of Audiology and Speech Pathology Services at Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center in Augusta, GA. She has completed the American Institute of Balance’s Certification in Vestibular Assessment and Management and Acumen Academy’s Introduction to Human Centered Design. Dr. Milnes enrolled in the Master of Healthcare Administration program through Colorado State University: Global Campus to develop leadership skills and networks to grow audiology and speech pathology into more prominent roles in medical settings by emphasizing the foundations of health that our services provide including communication resources, balance assessment and support, and cognition care in addition to initiating opportunities for growth through identification and prevention of hearing loss and fall risk through electronic health record identification factors.

Amyn M. Amlani, PhD, is the Director of Professional Development & Education at Audigy, a data-driven, management group for audiology and hearing care, ENT group, and allergy practices in the United States. Prior to this position, Dr. Amlani was an academician for nearly two decades. He also serves as section editor of Economics for Hearing Health Technology Matters.

Great article! Well done Kate, Trisha & Amyn!

Thank you, Angie!