These are the best of times and the worst of times, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us. (channeling Dickens for Audiologists)

Audiologists may agree that we are living in extreme times. It’s gratifying to practice our profession in the “communication obsessed 2000s” (Ridley, 2010), with ear-level devices at hand as the obvious portal for satisfying communication needs on a continuous basis.

It’s horrifying to witness a host of suppliers, including health insurance companies, opportunistically flooding the market with low-cost, middling devices with little regard to fit or function.

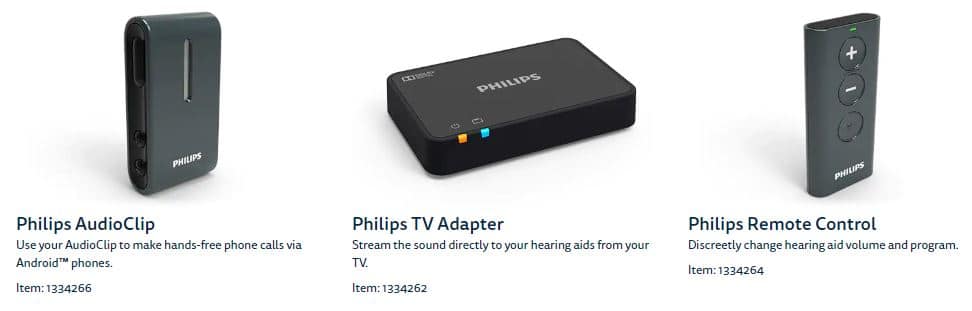

A Tale of Two Hearing Devices

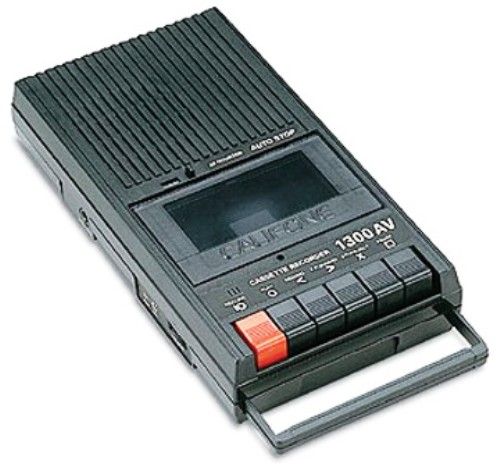

Auditory wearables got their start in the 70s with cassette players in the consumer electronics industry (Fig 1). Since then, they’ve progressed through successive hardware iterations, each smaller, more portable, and more functional than the last. Hearable wireless earpods with Bluetooth connectivity are one more step in the trajectory.

But wireless Hearables are a particularly noteworthy step because they begin to approximate part of the Holy Grail of wearables. Borrowing from Wearables imagery, truly wearable computers should feel like skin, offer a synced lifestyle, be extensions of ourselves, be part of being human, act as our third pair of hands. Whatever the metaphor, the two-fold, so-far unrealized, goal of Wearables and Hearables is to fully integrate with and enhance the wearer in as many ways as possible.

Hearing aids started over 100 years ago in an industry that can loosely be called medical electronics. Since then, they too have progressed through successively smaller, more portable and more functional iterations. Modern hearing aids with connectivity and cochlear implants closely approximate Wearables’ goal of full integration and enhancement of users, especially those who communicate wirelessly with smart phones.

But hearing aids fall short of other Wearable goals, including widespread use, acceptance, and multifunctionality. Stigma, price and regulation remain formidable obstacles to their widespread consumption. Hearing aid manufacturers are understandably cautious about expanding into mass-produced, low-priced consumer ear devices. Audiologists are understandably cautious and conflicted about fitting or supporting consumer electronics.

As Hearables gain momentum, pressure will grow on hearing aid manufacturers and Audiologists to adapt their goals in order to remain viable. The Wired quote from last week bears repeating and expanding:

Hearing aid devices and Audiologists are prime for disruption — respectively, they are a high-cost single-value product and a profession that can and should do so much more.

Leveraging a Hybrid

Instead of two extremes, why not hybridize Hearables on a hearing aid platform and fit them to a broader market? It’s not a new concept. Researchers at Helsinki University of Technology had this to say about it in a paper published in 20041:

We may have multiple wearable audio appliances, but only one pair of ears. At some point it makes sense to integrate all of these functions into the same physical device. Mechanical and electrical integration is already feasible. However, in application scenarios there are many interesting new possibilities and problems to explore.

Note the similarity between this view, from a Laboratory of Acoustics and Auditory Signal Processing, and this market-savvy view on Twitter:

Why hearables are the best form of wearables. A new category of wearables — “hearables” is making strides, leveraging a mainstream consumer accessory: the ear bud.

Beyond short-term profits and profiteers, leveraging ear buds makes sense for the excellent reason that it taps into an existing market that is eager to expand to full-time use of ear-level wearables. Power and comfort remain formidable obstacles to full-time use and widespread consumer adoption of accessories, which is the niche filled by present day ear buds.

It makes more sense to leverage a specialty consumer necessity: the hearing aid. At least one of the Big 6 is positioned to hybridize. GN Store Nord has headset (Jabra) and hearing aid (GN Resound) businesses. Its operations were described by Bloomberg as providing “hearing aids and hands-free communication products worldwide.”

The Economic View

Hybridizing for multifunctionality offers a view of a better, bigger Demand curve for the future, made possible by technological advances enabling diverse, global supply chains offering huge varieties of ear-level features at a much broader array of prices, thereby increasing Utility for more consumers. On the Supply side, the view is fraught, as experienced, technologically sophisticated companies like our Big 6 weigh the opportunity cost of expanding into Hearables while continuing R&D momentum and growth in high-level hearing instruments. The former requires direct-to-consumer and Big Box distribution with lowered margins; the latter is best served by professional fitting distribution with high margins at every step in the channel.

Servicing diverse distribution channels is politically tricky and economically challenging for hearing aid manufacturers. Consider the heated audiology response, and rumored boycott, after Phonak’s entry into Costco in 2014. Consider the nascent chatter already underway regarding GN Resound’s announcement of its extended and “strengthened” partnership with Costco. Unconfirmed rumors are flying, most prominently that LiNX will be a Costco staple, priced around $1000/aid.

Which brings this post to a close with a few economic thoughts on the Goods market side, where Audiologists and others sell product at retail.

- Audiologists are not loving premium instruments in Big Boxes anymore now than they did some years ago when the trend started.

- Audiologists don’t love PSAPs either, having shown little if any inclination to expand their offerings by adopting price-lining strategies to appeal to a broader consumer market.

- PSAPs and e-tailing are familiar trends at this point, with e-tailers themselves expressing “surprise” at Audiologists’ economic passivity:

“Audiologists have not pushed back much against online sellers of hearing technology, as they seem to serve different demographics of users—for now.”(quote from Patrick Freuler, Audicus founder. )The “for now” part sounds ominous, forecasting a future Demand curve battleground where Audiologists either fight for turf or retreat to a highly-specialized ivory tower in which diagnostics and treatment services are protected (e.g., pediatric audiology, cochlear implants). Fortunately, that’s the logical extreme, not real life. Hybridizing our practices while we await hybridized products offers a middle ground which can make sense economically: not the best or the worst of times, but the “good enough” times.

As it happens, “Good Enough” is the theme of an upcoming post by Brian Taylor.

This is the 6th post in the Hearable series. Click here for post 1, post 2, post 3, post 4, or post 5.

References

1Harma A, et al. Augmented Reality Audio for Mobile and Wearable Appliances. J. Audio Eng. Soc., Vol. 52(6), 2004.

image courtesy of strange history

For me the holy grail would be being able to buy a pair of top of the range smartphone comparable hearingaids for the price of an iPhone (around £500).

At this price, I think many baby boomers (ie those a few years older than me) might be tempted into private hearing aid providers.

However, as long as the choice is Free (and totally adiquate) NHS aids verses £2-3000 hearing aids which will be obselete next year I’m not interested.

It doesn’t matter what you call them, the things I stuff in my ears to hear the world better, should not be treated so very differently from glasses or mobile phones. I need to be able to upgrade them every two years and not be scared to use them.