by Holly Hosford-Dunn, PhD and Amyn Amlani,PhD

The Pricing series revs up for a multi-year update today, just in time to get in on the PCAST and IOM action of recent days and await signs from the FDA. In 2013, the announced intent was to “dive down and muck around with Price to test accepted assumptions.” Time for more diving and mucking in 2016, aided and abetted by series’ co-editor Amyn Amlani, PhD.

” Hearing Economics insists on careful evaluation of available data before agreeing that it’s a war out there. This requires tiny steps and lots of time, not to mention big assumptions based on incomplete data. No one said Economics is fun but it does strive to remain calm, wash away the hype, and mine for morsels of truth.” (previous Pricing post)

Let’s start with assumptions, then and now.

Hearing Aid Pricing Assumptions, Untested but Accepted as Fact

Universal assumptions come from the gut with no data-check from the brain, even when they are at odds with one another. These “mental shortcuts,” referred to by behavioral economists as heuristics, enable people and policy makers to decide and proceed, though often with inadequate information and biases.

Maybe the assumptions are right, maybe they’re not, but they’re what we believe. The following ones are familiar to all of us, they’re not going away, and they’re still as strong as they were in 2013.

Hearing aids cost $6000/pair

$6K has been the anchor price for more than a decade and serves as the rallying point for public outcry that hearing aids are too expensive for most who need them. Never mind that the price hasn’t gotten off the dime in 15 years, isn’t representative of actual Price in the US hearing aid market, and overlooks professional services bundled into the figure. $6K is the price that’s anchored deep in our cognitive and emotional brain tissue, producing reader Comments like this one in response to a PCAST post at the HHTM site:

How loudly do I have to SHOUT hearing aids are ridiculously overpriced. $2-6000 is a lot of money even to a high income household.

Hearing aids are an undifferentiated product

Yes they were largely undifferentiated before the 90s. That changed in 1994, when CICs came on the scene and the average Price of hearing aids began rising faster than inflation. Digital instruments appeared two years later and the industry never looked back.

Advancing through overlapping generations of digital signal processing, new technologies took on a host of hitherto insurmountable problems, including feedback and , environmental noise. Technological solutions enabled increasing range of product offerings including open fits that reduced occlusion, discomfort, and stigma. Recent wireless innovations continue the fast rise of product differentiation in the industry.

Notwithstanding all that, the image of a hearing aid remains undifferentiated in the minds of many, manifest in Comments like this:

Compared with… other consumer tech we all use every day – a state of the art hearing aid isn’t very clever, it amplifies, does a bit of graphic equalizing to boost HF a bit and is fairly small.

Hearing aids costs less than $100 to make

$100 has achieved anchor status in our industry. Harvey Abrams effectively abolished the claim in a previous post but that didn’t eliminate the assumption for those with confirmation bias, which is pretty much everyone not involved in making hearing aids. Hence, Comments like this remain common and reinforce the assumption:

If hearing aids cost the few $100 they should, better off people might decide it was worth the risk to buy a hearing aid.

Hearing aid prices are always rising

This assumption is easy to measure but hard to interpret. Whether the assumption is right on not depends on whether inflation, technological innovations, and product range are factored into Price. It’s simplistic and misleading to show a graph in nominal dollars that proves today’s premium products are priced higher than undifferentiated product in the 1990s, but that is the mental arithmetic which underlies the assumption and prompts Comments like this:

The hearing aid industry uses every new thing like digital or a new algorithm to raise prices.

Retail markup on hearing aids is exorbitant, exceeding 5x cost of goods

5x Markup may be on its way to becoming yet another anchor bias. The assumption is less measureable than Price because businesses don’t like to share operating numbers and few unbundle product from services. It’s also more mutable, depending on whether all costs of goods and services are included in the markup calculation. They should be but mental shortcutting often leaves them out of the equation and spits out erroneously high markups.

In fact, the 5x markup estimate is roughly twice actual markup. The assumption persists, disregarding fact, manifest in authoritative statements like this one which miraculously combines multiple anchors, assumptions, and confirmation bias into a concise, damning, but misleading statement:

The manufacturing cost of a typical high-end hearing aid is less than $100, and the wholesale cost is around $500. Any system that charges customers $5,000 for hearing aids is a broken system.

Dispensers and audiologists push high-end product to boost their bottom lines

The assumption that steering consumers to higher priced premium hearing aids improves profitability seems logical, albeit unethical, on the face of it. Ethics aside, evaluating the veracity of the assumption requires knowledge of wholesale and retail Price for differentiated categories of goods.

A previous post reported that premium products comprised no more than 30% of the overall retail market and generated lower percentage gross profits than below-premium products. The dollar markup for all product levels was about the same, suggesting that professional services were similar for all aid types and bundled in accordingly. Hence, markup did not appear to provide an incentive for professionals to push high-end products, unless they offered more benefit to individual patients.

Notwithstanding the data, the assumption is strong that premium product is the go-to place. Premium-priced products are anchored in the minds of consumers and authorities who influence social policy, if not in the minds of practitioners. This failure of a meeting of the minds prompts puzzled Comments from the latter group:

… odd that PCAST used an average cost per aid of $2400, which might on the high end, according to the same group that conducted the referenced survey. Why would affordability be based on that number, rather than a number from the lower end of the range?

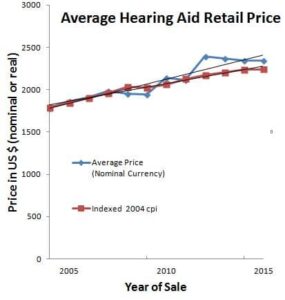

In fairness to PCAST and the Commentator, PCAST’s choice of average price was close to target (see Fig 1 below), despite or in addition to other data available to the council.

Assumptions, Tested, Accepted or Discarded

Figure 1. Average retail price of hearing aids in US, 2004 to 2016, shown in nominal and inflation-adjusted dollars

The header forecasts future posts in the series, but Figure 1 is a teaser of data-to-come. Dollars are pegged to 2004 instead of 1980 as in the 2013 Price series. That’s for two reasons: 1) to reflect change in the modern digital and RIC age of products and 2) because wholesale data aren’t available prior to 2004.

Without going into details reserved for future posts, two assumptions can be tested, accepted or rejected right away.

- Hearing Aid Prices are Rising. Accept and Reject.

Yes, along with everything else. Since 2004, overall retail hearing aid Price rose slightly more ($47/year) than the proverbial consumer basket of goods measured by the Consumer Price Index ($42/year). No, at least not since 2012. Retail Price peaked in that year and has declined or leveled off since. - Hearing Aids Cost $6K. Reject.

No, they don’t now and they never have, at least in the bundled aggregate. Consumers paid $2347, on average, for a hearing aid in 2014 and 2015, about $4700/pair.

Who Ya Gonna Believe – Data or Assumptions?

Readers may wonder how the $6K-and-Rising Assumptions work with premium product pricing. They may wonder about Price for “basic” instruments in today’s market. They may wonder about wholesale pricing and markups. And above all, they’d probably like to know where the heck the numbers are coming from for Fig 1 and future figures, before they are willing to believe analyses that purport to evaluate the assumptions.

As this series unfolds throughout the summer, posts will explore all those questions by using and sharing whatever data we can get our hands on.

This is Part 1 of the 2016 Hearing Aid Price Series update. Click here for Part 2.

Co-editor Amyn M. Amlani, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor on the faculty of the Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences, University of North Texas. Dr. Amlani holds the B.A. degree in Communication Disorders from the University of the Pacific, the M.S. degree in Audiology from Purdue University, and the Ph.D. degree in Audiology/Psychoacoustics (minor in Marketing and Supply Chain Management) from Michigan State University. His research interests include the influence of hearing aid technology on speech and music; economic and marketing trends within the hearing aid industry; and playing bass guitar with The Moonlighters, a heavy metal cover band.

*images courtesy of pinterest

Nice job. Clear, concise. I like your points on differentiation and pricing. Costco has reset the baseline, and there’s no going back. It’s just a question of how much, and how fast.

Nicely done article, Holly. I’ll be incorporation some of this into my community presentation on “How to Buy a Hearing Aid”, as price is always a major consideration.

Great post Holly – a major problem is that groups like PCAST have incorporated these assumptions into their recommendations, and it’s looking more like policy decisions are going to be made based on false assumptions.

The thought of that is so disheartening. But then how do we stop that from happening? Who is going to educate those who make the final decision?