Earmolds for hearing aids have been a staple for many years, made from impressions of the ear. Although considerable information exists about the earmold, the finished product, early ear impression history is murky. What we do know is that ear impressions took their lead from impressions of the teeth (dentistry), following somewhat later.

The contribution of dentistry to hearing aid fittings comes primarily through the application of impression material used to cast prostheses of the teeth. With hearing aids, the issue was not to cast a prosthesis, but to cast a coupler to connect the hearing aid to the ear, and to make this in such a way that it was comfortable, directed sound toward the tympanic membrane, helped to manage acoustic feedback, was cosmetically appealing, and fitted to the concha and distal portions of the ear canal. To manage this, the logical direction was to design this coupler in such a way that it duplicated the concha and the most external parts of the ear canal. And the best way to do this was to make an impression of the desired anatomical area. Fortunately, dentistry had worked out a number of impression solutions long before hearing aids reached this level of sophistication. The hearing aid industry took advantage of dentistry’s impression contributions.

A previous post initiated a timeline of impression materials used in dentistry. This post will continue the timeline, but reporting from the first indications of the use of impression material to cast an earmold. As mentioned in a previous post, no systematic history exists for the early days of ear impressions. This series of posts is intended to shed more light on the timeline of ear impression materials – not on the finished product, the earmold.

From Teeth to the Ear

1890 – First reported earmolds made from impressions of the ear

Figure 1. Thomas Hawksley of England manufactured non-electric ear-level metal cups that had custom earmolds attached to them in 1890.

Thomas Hawksley of England manufactured non-electric ear-level metal cups that had custom earmolds attached to them1. Berger writes that these were made by making wax impressions (Stents dental molding wax) of the concha and slightly inward into the external canal. Berger further describes the use of the wax impression, as follows:

“When the impression had been made and the excess wax trimmed off, it was coated with a metallic powder, and placed in an electro-depositing bath of copper sulfate, with a plate of copper as an anode. A thin coat of pure copper was thus deposited over the impression, and when it was sufficiently thick the wax was melted out and the pure copper surface was smoothed and polished (Silent World, May, 1957).”

It is not clear if the process described in the previous paragraph related specifically to ear impressions, or if this was the procedure used for dental models. Regardless, the process should have been the same.

Impression materials up to this date were rigid materials: plaster of Paris, impression compound, zinc-oxide eugenol plaster (a 1:1 paste ratio used only for very thin sections), and impression waxes.

1894 – Taking Impressions of the Mouth

James W. White wrote extensively on taking impressions of the mouth, and in doing so, provided much information about the materials used for impressions2.

“The substances or compounds in use differ widely in their physical characteristics, – wax, white and yellow; combinations of wax with paraffin; gutta-percha, and with other materials; modelling composition; gutta-percha, alone or in different combinations; plaster of Paris, alone or conjoined with the use of wax. …. Plaster of Paris is used almost exclusively by a majority of practitioners. Next in order as to the extent of use is modelling composition, then wax and wax compounds, and lastly gutta-percha.”

Beeswax

This should be a pure article, or that which has been judiciously combined with a foreign substance for a specific purpose. Alterations with tallow, resin, vegetable wax, etc., ruin it, making it difficult to manage. White wax is preferred over yellow in that it does not change shape, and takes a sharper impression than yellow2.

Modelling Composition

This material is composed of gum copal, stearin, and French chalk. It was available in several grades (soft, medium, hard, and extra-soft), with each having a different softening temperature and hardening time. Modelling composition could take a very sharp impression and was adaptable to irregular-shaped teeth, and regained its original form after displacement2.

Gutta-percha

Gutta-percha is a hard, tough, thermoplastic substance obtained from certain Malaysian area trees. It is a coagulated latex consisting chiefly of a hydrocarbon isomeric with rubber and is used currently in dentistry and for electrical insulation. It makes sharp and delicate impressions, but suffers from distortion upon removal, exposure to air, and contracts when cooled by air.

Plaster of Paris

This has been used for many years with fully established merits. The results are good to counter any inconveniences in use. It is chemically a native sulfate of lime, found in abundance in many parts of the world. In its crude state it is called gypsum, and is prepared for use by being reduced to a fine powder, and subsequently calcined in ovens 2.

1925 – Reversible hydrocolloid impression material – First flexible impression material

Reversible hydrocolloid was introduced to the dental profession in 19253 by Alphons Poller, an Austrian. It was patented as “Nogacoll,” but sold also in 1931 under the name of “Denticole.” The fundamental ingredient of hydrocolloid is agar-agar, a colloid obtained from seaweed. It was first used for making impressions of human faces in order to fabricate plaster reproductions, but was rapidly adapted to dentistry.

By 1935, almost a dozen competing brands were available. Still, a major dental textbook in 1932 indicated that modeling compound continued to be used extensively for impression making4. This reversible hydrocolloid impression material was often referred to as an elastic hydrocolloid. These had to be chilled to hold their shape.

1931 – “Stock” earpieces for hearing aids

At least by 1931, “stock” earpieces were made for hearing aids5. These consisted generally of anywhere from three-to-six different sizes (right and left ears), formed of hard rubber or Bakelite – fixed, unyielding. However, Lieber does not reference any ear impression material or procedure for the soft rubber flexible earmolds of his patent. We are left to assume that they were made using plaster of Paris or hydrocolloid. It appears also that custom earmolds were not yet in vogue.

1941 – Irreversible hydrocolloids (alginates)

These rubber elastic materials were developed during the World War II era, or just before, and introduced to the dental profession in 19436 for impression taking. These were developed because agar-agar had become scarce, with most of it coming from Japan. Irreversible hydrocolloids, known as alginates, were developed from seaweed and were salts of alginic acid, such as sodium alginate. Some of the alginates used were: Zellex, Imprex, Tissutex. A problem with alginates was that they had to be sent in a moist condition to avoid shrinking.

Hydrocolloids are considered elastic materials.

1946 – Acrylic material for ear impressions

Figure 2. Acrylic ear impression material. This consisted of a powder (container jar on left), catalyst (can), and a cup in which the ingredients are mixed using a metal spatula. Audalin brand made by the Audiplast Division of Coe Laboratories. This was an ethyl methacrylate mixture.

Berger1 reports that acrylic materials used to make ear impressions were introduced about 1946, but that plaster of Paris impression material was still used throughout the 1940s. Acrylic material consisted of a powder and liquid combination, mixed together to provide the impression material (Figure 2). This was initially made available in bulk quantity.

1950s – Powder and Liquid (Acrylic Material)

Powder and liquid impression material was still a fairly new and technologically advanced process for taking ear impressions in the late 1950s7. This combination had a long life in taking ear impressions, primarily from the late 1940s and continuing at least into the early 1980s, but with the bulk coming in the 1960s and 1970s.

Plastic powder and liquid is commonly known also as ethyl methacrylate, which is a monomer-polymer dough process. It has also been identified as acrylic material, traditional material, or liquid and powder material8.

Not everyone made a rapid transition to this new ear impression material. Mark Ross, Ph.D. reported having plaster of Paris ear impressions made for his first issued hearing aid at Walter Reed Army Hospital in the 1950s, and that he made his first ear impressions even later, as an audiologist, of plaster of Paris9. This seems a rather late use of plaster of Paris for making ear impressions, but may reflect the fact that audiology had not yet made any significant inroads into the actual dispensing of hearing aids.

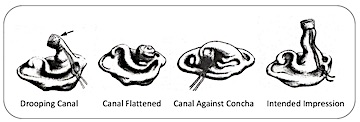

While quite an improvement over previous impression materials, powder and liquid was not without its drawbacks7. The monomer and polymer would shrink over time, resulting in an impression with a useable life span of only about 30 days. Also, the original product was sold in bulk, and as such, professionals used quite a bit of freedom in adjusting the powder to liquid proportions. This resulted in interesting changes in the shape of the cured impression during transit to the lab, especially in hot weather (Figure 3). The author can attest to this having seen many ear impressions looking this way when they arrived at the Audiotone facility in Phoenix, Arizona, especially during the summer.

Figure 3. Examples of the effect of heat on powder and liquid ear impressions resulting from inappropriate quantities of powder and/or liquid

Powder and liquid ear impressions dominated during the 1960s and much of the 1970s.

Figure 4. Acrylic ear impression kit. This consisted of a powder (brown container), catalyst (clear bottle with red cap), a paper cup in which the ingredients are mixed, using a wooden spatula (in bag), otoblocks and Q-tip also in the bag, and a self-mailer container in which to send the impression to an earmold laboratory where the earmold will be made.

This issue of bulk use was addressed by packaging powder and liquid in controlled proportions (Figure 4). Still, even with this improvement, additional variables came into play: the mix time, the promptness of loading the syringe or preparing the hand method mixture, and even the tools used to mix the material. For example, the use of a paper cup and wooden tongue depressor tended to absorb some of the liquid, resulting in variations in the formula. Preferred mixing tools recommended were a glass bowl and a metal spatula.

Elastomeric Materials

Elastomeric impression materials for dentistry were introduced in the 1950s and 1960s. Examples included: elastomers, polysulfides, polyethers, addition silicone, and condensation silicone. (These did not make an impact into ear impression use until the 1970s).

Elastomers are used for ear impressions. They have flexibility or elasticity against breaking or cracking, and do not melt when heated. The primary type used for ear impressions is silicone.

1953 – Polysulfide impression materials

These were elastomeric impression materials – a synthetic rubber or other polymer in which the units are linked through sulfur compounds. Until the introduction of polysulfide impression materials, hydrocolloids were the only elastomeric impression materials available to operative dentistry and prosthodontics10. Even though these were messy to work with and relatively sensitive to distortion, they offered much more strength than the hydrocolloid material. If used for ear impressions, this writer found no specific reference. The same holds true for polyethers.

1955 – Hallowell Davis wrote:

“An earpiece is made by first taking an impression, or cast, of the ear, either with plaster of Paris or with a special elastic plastic. In the larger cities some dealers in hearing aids can provide this service11.”

It appears that Davis was referring to hydrocolloids as the “elastic plastic,” based on what some hearing aid dealers were using at the time.

Instant, and Elastomeric Impression Materials

Instant Earmolds – Impression Becomes the Earmold

Early instant earmold materials, resulting in a finished earmold, fell into three types: acrylics, silicones, and synthetic rubber polymers, in order of their chronological introduction7.

1957 – Hard acrylic instant earmolds

This was presented to the market by Adcomold, and resulted in a finished earmold fabricated from the impression itself.

1958 – Soft earmold

A soft earmold, made from the impression, was Introduced to the market by Adcomold a year after they introduced their hard acrylic instant earmold.

As mentioned earlier, examples of elastomeric impression materials include: elastomers, polysulfides, polyethers, addition silicone, and condensation silicone. Silicones appeared in the mid-to-late 1960s as ear impression material, although it had been present in the dental industry the preceding decade.

A following post will take the history of ear impression materials from the 1960s through the current date.

References

- Berger, K.W. The Hearing Aid: Its Operation and Development, 1974 Revised Edition, p. 117, National Hearing Aid Society, Livonia, Michigan.

- White, J.W. Taking impressions of the mouth. The Dental Cosmos, Vol. 36, #1, January. (Similar to an earlier publication having the same title, in 1871).

- Asgar, K. Elastic impression materials. Dent Clin N Amer 1971; 15(1): 81-98.

- Gillett, H.W. and Irving, A.J. Gold inlays by the indirect system. Brooklyn, Dent Items Interest Pub Co, 1932.

- Lieber, Hugo. Earpiece for ear phones, US Patent No. 1,893,474. Files, May 27, 1931; granted Jan. 3, 1933.

- Hansson, O., Eklund, J. A historical review of hydrocolloids and an investigation of the dimensional accuracy of the new alginates for crown and bridge impressions when using stock trays. Swedish Dent J 1984; 8 (2): 81-95.

- Cartwright, Karl. 2009. 50th anniversary reflections, West Tones, October, Colorado Springs, CO.

- Pirzanski, C.Z. Earmold acoustics and technology, in Hearing Aid Amplification, 2nd Ed. (Sandlin, ed.), Singular, San Diego, p 141.

- Mueller, H.G., Bentler, R., and Ricketts, T.A. Modern Hearing Aids Verification, Outcome Measures, and Followup. Plural Publishing.

- Coy, H.D. The selection and purpose of dental restorative materials in operative dentistry. Dent Clin N Amer 1957; 1 (1):65-80.

- Davis, H. Hearing and Deafness, A Guide for Laymen. 1955. Rinehart & Company, Inc., New York. P. 191. (First printing, 1947).