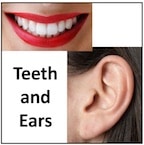

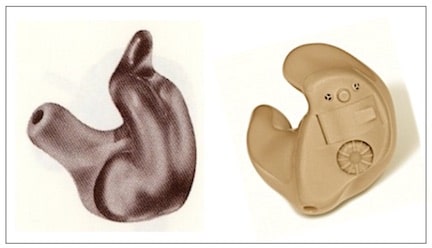

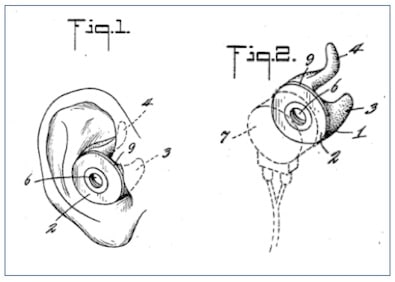

An ear impression has most often been used to fabricate an earmold (earpiece) that fits into portions of the outer ear to direct amplified sound toward the tympanic membrane (Figure 1). Essentially, an ear impression is made by placing a viscous, thixotropic impression material into the concha and part of the ear canal. When it sets to become an elastic solid, it is removed and should provide a detailed and stable negative.

Figure 1. Ear impressions are used to fabricate earmolds for many hearing aids, as in those shown here for a behind-the-ear (BTE) and custom-molded in-the-ear (ITE) on the right.

Interestingly, there seems to be no systematic recorded history of the development of ear impressions, even though the taking of ear impressions has been used for at least the past one hundred years in order to make earmolds/earpieces for hearing aids. That the earmold, and as a product of an ear impression is important, can be summarized in the following statement.

“The earpiece is often the harbinger of unsuccessful hearing aid use because of its intertwined relationship to acoustic feedback, the occlusion effect, discomfort, cosmetic concerns, remakes, patient listening downtime, cost, etc. The earpiece plays a major role in issues related to the problems or success of wearing hearing aids1.”

Ear Impression Background

Figure 2. An artificial concha designed and molded for an individual user, would have been worn as a self-retaining adornment that could blend in with a hairstyle or jewelry. (Bernard Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine).

An early reporting of a listening device that was said to be custom-designed and molded for an individual user (Figure 2), originated from about 18302. This was fabricated by F.C. Rein (London), and consisted of gold-plated silver with a filigreed grill covering. By 1830, wax and plaster of Paris were already used for impressions of the teeth. It seems likely that these materials could have been used to make a cast of the ear as well, although this is reasoned speculation.

Figure 3. Halsey A. Frederick patent for a custom earmold in 1926, attached to a button receiver/speaker. Although made as a custom earmold, the patent teaches nothing about the procedure for taking the ear impression. The history of ear impression procedures was earlier, about 1980.

History records that Halsey A. Frederick received the first U.S. patent for a custom earmold in 1926 (#1,601,063), but the patent taught nothing about the procedure for taking the ear impression3. The patent was assigned to Western Electric Co., and the earmolds were fabricated under license by the S.S. White Dental Manufacturing Company of Philadelphia (Figure 3). Likewise, a first patent for a soft, non-custom earmold was granted to Hugo Lieber of the Sonotone Corporation, a hearing aid manufacturer, in 1933 (US 1893474)4. The earmold was not custom, having been designed in three different sizes.

Figure 4. Hugo Lieber patent of “stock” hearing aid earmolds, made of flexible material (such as soft rubber) that may yield somewhat and thereby adapt to the individual ear, and to reduce the number required to three

“Stock” earpieces were made for hearing aids at least by 19314. Lieber reported that “stock” earpieces consisted generally of anywhere from three-to-six different sizes (right and left ears), formed of hard rubber or Bakelite – fixed, unyielding forms. Lieber’s contribution related to a patent intended to improve earpieces for hearing aids using a flexible material (such as soft rubber) that may yield somewhat and thereby adapt itself to the individual ear, and to reduce the number required to three (Figure 4).

As like Halsey, Lieber does not reference any ear impression material or procedure. We are left to assume that they were made using plaster of Paris or hydrocolloid, common materials for ear impressions used at the time.

However, first U.S. patents provide no confirmation that other custom earmolds had not already been made. And besides, the intent in this post is to determine the origin and history of ear impression materials and procedures, a necessary component of any custom earmold.

As stated, this post is more interested in the history of impression materials used for taking ear impressions, and any related procedure used for its insertion, and not on the specifics of the procedure (preparation, placement of otoblock, etc.).

The Contribution of Dentistry to Hearing Rehabilitation

History shows that the taking of ear impressions, and the materials used, followed that of the dental profession where impressions were made to provide models and prostheses of the teeth, but, records are sketchy.

Timeline of Impression Materials

1684 – Wax of unknown type, but most probably, beeswax.

A first description of using wax impressions for modeling prosthetic appliances was reported to have been made by Matthaus Purmann (1648-1711), a German surgeon5.

1700s (mid-to-late) – sealing wax, softened in water

The use of impressions, specifically related to teeth, has been credited to another German, Philipp Pfaff (1713-1766), a dentist to Frederick the Great of Prussia (mid-to-late 1700s)5.

1787 – Beeswax

Isaac Greenwood’s ad in the New York Daily Advertiser – “persons at any distance may be supplied with artificial teeth by sending an impression, taken in wax, of the places where wanted…”5

Wax is a poor impression material by today’s standards, but it seemed to have functioned adequately in its day.

1820 – Plaster of Paris (Gypsum)

Isaac John Greenwood and bother Clarke (sons of Isaac Greenwood) are reported to first use plaster of Paris (so named because one of the most extensive deposits was found in the “Paris Basin,” near Paris, France) in 18205 for dental work, but its first use as impression material is uncertain. One source traces it roots to the very early 1800s6, but the use of Plaster of Paris was well-established for taking dental impressions by 1844, and was the most commonly-used impression material in 19047. It seems certain that plaster of Paris was first used to pour up dental impressions before it was used as an impression material. Although plaster was an accurate impression material, it had the distinct disadvantage of being inflexible, typically fracturing during removal.

1835 – Wax, usually beeswax

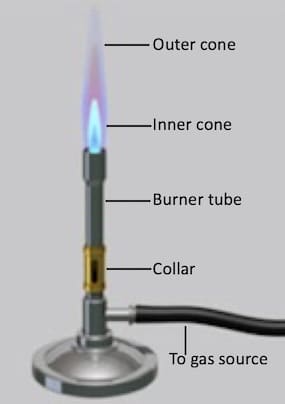

Figure 5. A Bunsen burner named after Robert Bunsen, is a common piece of laboratory equipment that produces a single open gas flame, used for heating, sterilization, and combustion.

In A System of Dental Surgery by Samuel Sheldon Fitch, he writes that one should take a piece of wax, usually beeswax, and to soften it in warm water on in a flame, after which it is pressed on the teeth and gums8. He says that this will give “an exact impression.” A Bunsen burner or a spirit stove was used to soften the wax for insertion (Figure 5).

1847 – Gutta-percha

This is a natural latex obtained from tropical trees native to Southeast Asia and northern Australia. It was introduced by Edwin Truman as a material for making dental impressions, but it was not very satisfactory for the intended purpose because it had a tendency to distort upon removal from the patient’s mouth, and to shrink upon cooling.

1856 – Stent Modeling Wax

Charles Stent, an English dentist, developed an impression (modeling) compound as an attempt to improve gutta-percha by adding stearin, a substance made from animal fat, to improve plasticity and stability. He also added talc as an inert filler to strengthen and “add to the texture” of the material, and a red coloration9,10. This became a common thermoplastic molding material to use for making impressions. Hot water was required to soften the wax for insertion. A major problem was that the impression shape was distorted upon removal.

1871 – Taking Impressions of the Mouth (republished in 1894)

James W. White. Used wax and plaster of Paris.

Next week’s post will take dental impressions to ear impressions – Impressions: From Teeth to the Ear – the Start

References

- Staab, W.J. 2014. Hearing aid evolution VI – hearing aid coupling, https://hearinghealthmatters.org/waynesworld/2014/hearing-aid-evolution-vi-hearing-aid-coupling/.

- Bernard Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine.

- Halsey, A.F. 1926. U.S. Patent No. 1,601,063, Acoustic Device.

- Lieber, Hugo. Earpiece for ear phones, US Patent No. 1,893,474. Files, May 27, 1931; granted Jan. 3, 1933.

- American Academy of Dental Science. A History of Oral And Dental Science In America. Philadelphia, Samuel S. White. 1876. p. 47.

- Ward, G. Impression materials and impression taking – an historical survey. Dent. J. 1961; 110 (4): 118-19.

- Prothero, J.H. Prosthetic Dentistry. Chicago, Prothero, 1904.

- Fitch, S.S. A system of dental surgery: in three parts. G.& C. & H. Carvil, New York.

- Harris, C.A., Gorgas, F.J.S. Dictionary of Dental Science. Philadelphia, P. Blakiston, Son & Co., 1891.

- Ring, M.E. How a dentist’s name became a synonym for life-saving device: the story of Dr. Charles Stent. History of Dentistry; 49 (2): 77-80.