Open Earmold Hearing Aid Fittings

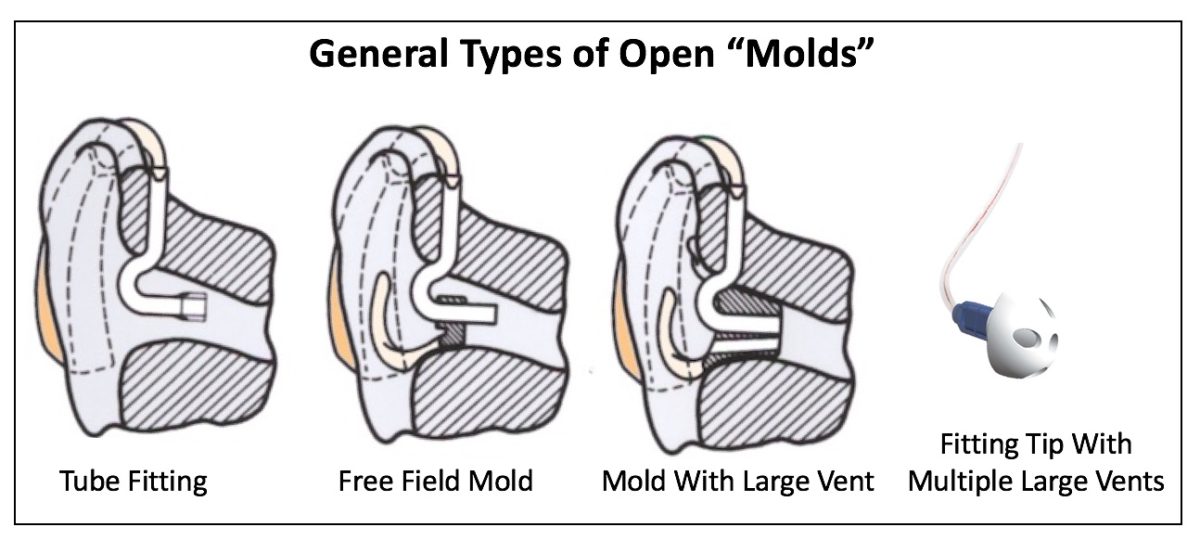

Open earmold fittings (essentially, ear pieces having a single large vent, multiple vents, or tubing alone), are commonly used today to achieve a successful fit for the hearing-impaired population having high-frequency hearing loss (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Open earmold fitting variations, left to right. a) tubing only, b) free field mold – open tube with retainer for security, c) mold with large vent, and d) a RIC (Receiver-in-canal) style multivented “stock” tip.

How and When Did Open Earmold Fittings Come About?

It is unlikely that the person who coined the term, or even the actual year in which it came to be in use, can be identified with certainty. However, the term “open mold” and its use was in effect at least in the early 1960s, but became an industry practice following the introduction of the CROS (Contralateral Routing of Offside Signals) hearing aids (Harford and Barry, 1966), and to its later variation, the IROS (Ipsilateral Routing of Signals). For clarity, the IROS is an open fitting on the same side as the hearing aid – essentially, an open fit (unoccluded) hearing aid.

The popularity of departing from closed earmolds was well-entrenched by the mid 1970s, as evidenced by an entire Symposium devoted to earmold configurations at the Seventh Danavox Symposium of Earmolds and Associated Problems in Denmark (Dalsgaard, 1975). Many of the topics of this Symposium were devoted to the problem of measurements via couplers used at the time for unoccluded (open) coupling of the hearing aid to the ear. However, some of the presentations discussed and showed tube-type earmolds, using the words “open mold” or “open earmold,” along with fittings that used tubing only. It is obvious that not just the term, but the method of fitting hearing aids with some type of open earmold was an accepted practice by the early 1970s as seen in the quote that follows:

“Open earmoulds made up 16% of the total number of moulds made at the State Hearing Centre, Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark in 1971/72. They were referred to as open earmolds, and consisted of tubing placed in the ear canal.” (Nielsen, 1975).

It is factual that the practice of open, or unoccluded, molds was used and expanded upon with the IROS (Ipsilateral Routing of Signal). Curren ( 2014) wrote that open canal technology, as practiced then, “changed a lot of widely held assumptions, and brought to the fore many of the important understandings we hold today about providing acceptable amplification for high frequency losses.”

Figure 2. Zenith Radio Corporation Acoustic Modifier patented earmold.

An early approach at opening the earmold to assist high-frequency amplification by reducing low-tone over-amplification occurred in the late 1950s with the introduction of the “Acoustic Modifier” earmold by Zenith Radio Corporation (Figure 2). This was a short-canal, wide-bore earmold having one or more center holes about 0.1-inch diameter drilled into the enlarged canal of the earmold from the flat out surface, with each vent hole terminating in a disc of porous fabric to create a low-pass filter. And, Lybarger (1958) suggested that the use of vents and how they could affect the hearing aid response, can be an advantage of the user (1967).

It was known that opening the earmold could have benefit for individuals having high frequency hearing loss even prior to its use with CROS hearing aids (Lewis and Plotkin, 1962). Open fittings were expanded upon by others, showing a history of having evolved from small vents originally intended to reduce pressure sensation concerns, then larger to about 2 mm+ diameter to reduce low-frequency amplification and to reduce the occlusion effect (Curran, 1971; Lybarger, 1978; Wimmer, 1986; Revit, 1992; Wynne and Williams, 2001; Kiessling, et. al., 2003), to tubing only (Rowland, 1972, 1980; Courtois and Berland, 1972, 1973; Janssen, 1981 and Staab & Nunley, 1982).

Regardless, the real move toward open mold use followed the introduction of the CROS hearing aid. Current, accepted same-session RIC (receiver-in-canal) or RIA (receiver-in-aid)-style hearing aids often include open earmold (using an ear tip having multiple vents – Figure 1) technology, continuing this successful fitting practice.

Definition

The open or unoccluded type mold allows the tubing or a small diameter tip to project into the ear canal, leaving it essentially unoccluded (open). This type of mold is designed to keep the ear canal as unoccluded as possible (Lybarger, 1985).

Lybarger’s definition may not be the first written, but it generally defines the open mold.

Caveat

Large vented and tubing-only systems are applied reasonably well to post auricular hearing aids provided the hearing loss is not too severe, or the hearing aid does not attempt to combine high-frequency electrical emphasis with the large vent or tubing only. Large vents are not as practical for certain custom-molded hearing aids because the microphone and speaker are so close together, creating an opportunity for acoustic feedback. However, current feedback reduction circuitry allows for larger vents than previously.

What kind of products have called themselves open molds?

Most earmold laboratories had ‘open’ or ‘non-occluding’ earmolds back in the 1970’s and 1980’s and are common today. Some of these were referred to as tubing only, tube fitting, spider, IROS, JH mold, and so forth. Many names have been used to identify such a fitting, often taking on a name of the person who introduced the earmold, or given a name by an earmold lab or by a hearing aid manufacturing company.

References

Berland, O. (1973). No-Mold Fitting of Hearing Aids, Scandinavian Audiology Supplement 5, Earmoulds and Associated Problems, Seventh Danavox Symposium 1975, GL. Avernaes, Denmark.

Courtois, J., and Berland, O. (1972). No-mold fittings, I, Audecibel, Fall, 171-178, 180—181.

Courtois, J., and Berland, O. (1973). No-mold fittings II. Audecibel, Winter, 28, 30-32, 34-36, 38-39.

Curran, J. (1971). CROS fittings and open-canal amplification, with notes on Bi-CROS and Power-CROS, Dahlberg Electronics, Inc. Monograph, Golden Valley, Minnesota.

Curran, J. (2014). How open canal amplification was discovered, Canadian Audiologist, Vol. 1, Issue 6,

Dalsgaard, S.C., (1975). Organizer. Earmoulds and Associated Problems. Scandinavian Audiology Supplementum 5, Seventh Danavox Symposium, GL. Avernaes, Denmark.

Harford, E., & Barry, J. (1965). A rehabilitative approach to the problem of unilateral hearing impairment: the contralateral routing of signals (CROS). Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 30, 121-138.

Janssen, G. (1981). Presentation on Tube Fitting at Audiotone Laboratory. Phoenix, Arizona, December, 1981.

Lewis, E. and Plotkin, W. (1962). The role of the acoustic coupler in hearing aid fitting. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the American Speech and Hearing Association, Chicago, Illinois.

Lybarger, S. (1958). The earmold as part of the receiver acoustic. Radioear Corporation.

Lybarger, S. (1967). Earmold acoustics, Audecibel, Winter, pp. 9-19.

Lybarger, S. (1985). Earmolds, Chapter 44, in Katz,, J. (Ed.). Handbook of Clinical Audiology, 3rd edition, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore.

Rowland, R. (1972). BIROS and tube fitting. National Hearing Aid Journal, 12:13, 36, 38.

Rowland, R. (1980). Tube fitting: myth, magic, or method. Seminars in Speech, Language and Hearing, 3:197-204.

Staab, W.J., and Nunley, J., “A Guide to Tube Fitting of Hearing Aids,” Hearing Aid Journal, September, 1982, pp. 25-34.