Legalized OTC (over-the-counter) hearing aids are coming as a new consumer option. One of the arguments against this practice is that the potential purchaser has not had an audiogram from which to determine the type and degree of hearing levels to assist in the selection of the appropriate hearing aid, if such is to be recommended.

However, serious discussion exists relative to the real value of a pure-tone audiogram for such selection, perhaps for the majority of individuals, especially based on the way pure-tone testing is currently conducted. What then, might be the role of a hearing self-test?

Predicting Hearing Level Without an Audiogram?

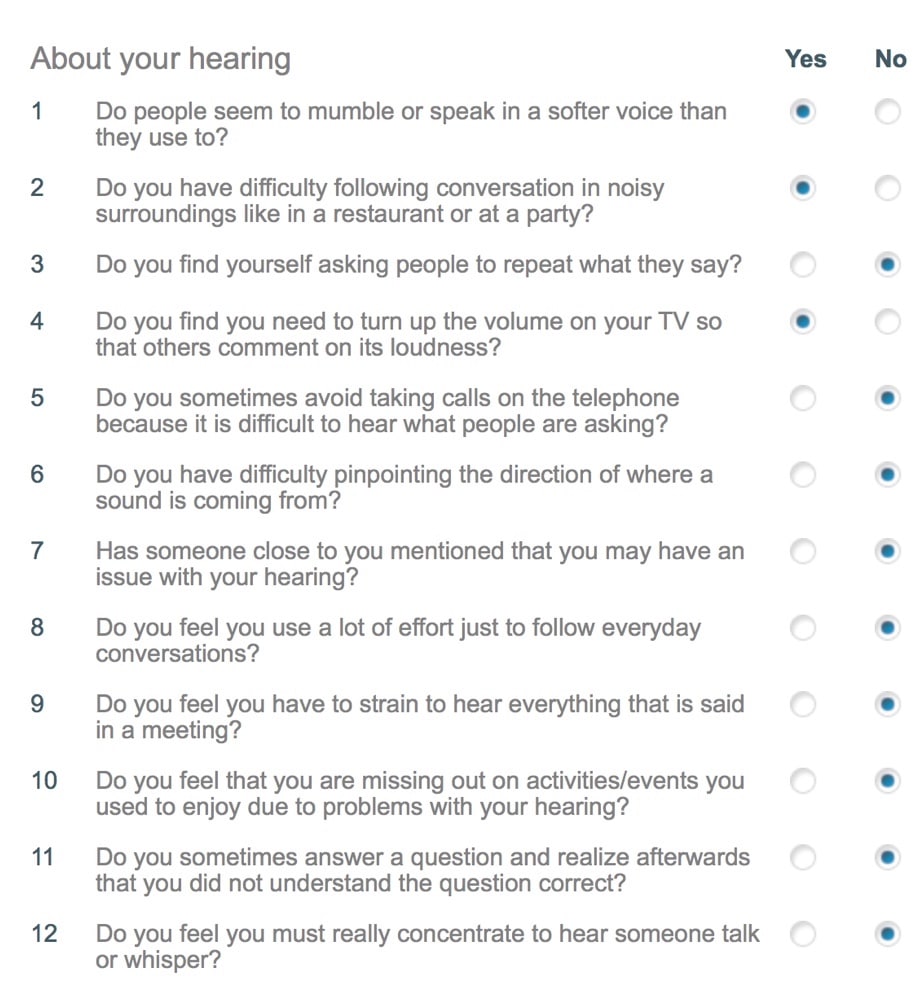

Aside from having an audiogram made, is it possible to somewhat “predict” an individual’s hearing levels? One skilled in the art can most likely draw a reasonable facsimile of a person’s audiogram just by conversing with them. Advertisements by both traditional and audiologist hearing aid dispensers have used paper and pencil questionnaires for years to “estimate” hearing levels in promotional materials to encourage consumers to utilize their services for more in-depth evaluation. An example of a common form is shown in Figure 1, where the consumer answers questions to determine and/or confirm that they have some hearing difficulties.

Figure 1. One form of likely hundreds of different paper and pencil hearing “tests.” Most, such as this one provided on the Internet, require that you provide your name, phone number, and other identification in order to get the “results.”

Other paper and pencil tests are more elaborate, such as the HHIE-S (Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Screening Version), suggesting handicap as either no, mild/moderate, or severe.1 But, the HHIE-S starts with the assumption that the person already recognizes and accepts that they have a hearing problem. Many other paper and pencil tests relate primarily to performance following hearing aid recommendation and use. A common format, especially online, is for the providing source to make a behind-the-scene decision based on questionnaire responses and requires that the consumer provide name, phone number, etc. in order to get the results. This last step discourages many who take the test from following through, realizing that this will result in being contacted to schedule an appointment (most likely). There is nothing wrong in using this approach.

However, what happens to those who choose not to be contacted? Why not provide them with a simple paper and pencil test (I use this term even though the test may be an online test that requires a mouse or key click to record a response) that gets at some kind of estimate of their hearing level? Keep in mind, however, it is reasonable to believe that a person taking a test that requires personal information in order to obtain the results, is more likely to minimize their level of difficulty as asked by the questionnaire.

“The availability of more elaborate paper and pencil tests, such as the HHIE-S, assumes that the individual already acknowledges their hearing problem. Many online tests require personal information, potentially leading individuals to downplay their difficulties. Providing a simple, anonymous paper and pencil test could offer an alternative for those who choose not to be contacted and allow for a more realistic assessment of their hearing level.”

Self-Test of Hearing – Paper and Pencil

A number of years ago this author designed a paper and pencil self-test of hearing. The test, in the form of a short questionnaire, was designed to allow a consumer to evaluate his/her ability to hear in different circumstances, and that their answers would help them better appreciate and understand their hearing status. They could make their own decision as to whether they wanted to follow through more specifically on the results of the test with whatever hearing testing facility they wanted. What the test was intended to do was to inform them about what they could expect of their hearing, based on their responses. Because the person knew that their answers were personal, and that no one else would see them, they were likely to answer the questions more honestly than those questionnaires that request their personal information in order to get the results. The intent of the self-test is to provide a rapid, but reasonably accurate understanding of the person’s hearing status.

Figures 2 provides the questionnaire and Figure 3 provides the scoring information. The degree of loss as identified from the scoring chart, is explained in the text following the two figures.

Figure 2. This page provides the self-administered questionnaire used to obtain information for the scoring sheet (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Scoring sheet for self-test of hearing. This scoring sheet was originally tied to different gains and responses for each of the shaded boxes for a specific manufacturer’s hearing aid products. It would seem that such a test and format could be used for OTC hearing aid selection.

Descriptions of Hearing Expectations Based on the Self-Test of Hearing Scoring Sheet*

Near Normal/Borderline (< 25 dB)

- Hearing handicap is questionable

- Still, some believe a hearing aid is critical to their work or learning environment

- Amplification, if accepted, will seldom involve more than part-time use

- Not usual candidates for amplification

Mild Hearing Impairment (26-40 dB)

- Slight handicap for some––significant for others

- May have difficulty hearing faint and/or distant speech but likely to “get along” in most situations

- Sustained attention is frequently difficult

- Speech and language is learned normally, monitored by traditional auditory feedback mechanism

- May or may not need amplification

- Most will find that HAs are too noisy unless:

- Some type of open canal fitting is employed

- Some unique noise suppression/cancellation approach is used

- If hearing aids are worn, they most likely are not worn constantly

Moderate Hearing Impairment (41-55 dB)

- Understand conversational speech at relatively close distances without great difficulty

- Under normal conditions speech may have to be repeated often

- Speech may show articulation problems (omissions, substitutions, and distortions of speech sounds).

- May benefit well from hearing aid use

Moderately-Severe Hearing Impairment (56-70 dB)

- Understand conversational speech only if it is loud and/or close in proximity

- Considerable difficulty expected in group or noisy situations

- Appear “not to pay attention”

- Enough hearing is present to learn or maintain language and speech through the auditory feedback mechanism when amplification takes place

- Excellent benefit from hearing instruments can be expected

Severe Hearing Impairment (71-90 dB)

- May hear sound or loud voice close to the ear

- Identify environmental noises, and may distinguish vowels but not consonants

- Seem to be “ignoring” communication

- Hearing aids enable them to become relatively functional for ordinary purposes of life

- Language and speech will not develop spontaneously in a youngster and may deteriorate significantly if the loss occurs over time, as with an adult

Profound Hearing Impairment (91 dB>)

- Do not rely on hearing as their primary avenue of communication

- Speech and language must both be developed through careful and extensive training since these cannot be learned by ear alone, even with amplification

- Hearing levels in this category are often identified in the “deaf” range

- Hearing aids are intended to allow the user to maintain contact with the environment and to allow the utilization of any auditory clues that might be presented

- Many do not utilize amplification, but rely on manual communication

Summary

A number of years ago, a University study compared the scoring results of this self-test with measured audiometric thresholds and found a high correlation to the hearing loss category identified. Unfortunately, the author lost the data. So, if anyone recalls this study, the author would be greatly appreciative.

**The hearing test, impairment descriptions, and images are provided courtesy of Staab, W.J. (2017). Hearing Aids: A User’s Guide, 4th Edition (in preparation).

References

- Ventry, I.M., & Weinstein, B.E. (1983). Identification of elderly people with hearing problems. ASHA, 25, 37-42.

Wayne Staab, PhD, is an internationally recognized authority in hearing aids. As President of Dr. Wayne J. Staab and Associates, he is engaged in consulting, research, development, manufacturing, education, and marketing projects related to hearing. His professional career has included University teaching, hearing clinic work, hearing aid company management and sales, and extensive work with engineering in developing and bringing new technology and products to the discipline of hearing. This varied background allows him to couple manufacturing and business with the science of acoustics to bring innovative developments and insights to our discipline. Dr. Staab has authored numerous books, chapters, and articles related to hearing aids and their fitting, and is an internationally-requested presenter. He is a past President and past Executive Director of the American Auditory Society and a retired Fellow of the International Collegium of Rehabilitative Audiology.

Pure tone audiometry provides an objective measurement of a subjective problem which is pretty impressive in my view. Until we can get inside another persons head and hear what they’re hearing audiometry will remain a valid tool for determining the start point for programming a hearing aid. We should however stop referring to it as “Gold Standard” and remind ourselves that it is long overdue for a radical re think. Measurement uncertainty resulting from poor calibration protocols, variable headband tension, eccentric earcup placement, poor adherence to Standards, physiological differences in the patient etc etc all need to be addressed.