Hearing-impaired individuals, and especially older adults, find it difficult to perceive speech, especially in noise conditions. Many turn to hearing aids to help resolve this difficulty. However, when they receive their programmed devices, the primary setting is for listening in quiet.

To help resolve this problem, most hearing aids today are programmed for different environmental listening conditions. It is common to see such programs listed, using slightly different terminology, as: listening in quiet, listening in noise, listening to music, listening in a restaurant, comfort, etc. Current hearing aids commonly offer 3 to 6 environmental listening options.

Still, annoyance of amplified sound through the hearing aid, due to circuitry noise and/or background noise, continues to be a major cause of hearing aid rejection. Research has shown that individuals with cochlear hearing loss (the most common type), require the primary signal to be attended to, to be much higher in level than background noise than is required for individuals having normal hearing1,2,3,4,5,6,7.

Listening in Quiet

Interestingly, the first setting for programmable hearing aids is generally for listening in a quiet environment. Why is this? Is this an attempt to assist the user to adjust to amplification, is it actually for listening in a quiet environment, or is it just following what has been done without asking why?

In bygone years of hearing aid counseling, patients were often provided a general timetable for listening events to occur. Such a training schedule started with quiet listening in the home (without radio, TV, or chatter of other people), and identifying the sounds around them. This exercise was repeated until the person could clearly distinguish the various types of sounds. From this point forward, the user would be introduced to increasingly more complex listening situations, but on a slow schedule, and with increasing wear time as they progressed. The trend was to “make haste slowly.” This was done to provide for an “optimal” initial listening experience.

Did this work, and do new hearing aid users follow such a training regimen? No evidence was found confirming that hearing impaired individuals actually followed such amplified listening progression schedules. It is suspected that then, as today, when individuals obtain hearing aids, that they attempt to wear them everywhere – immediately, regardless of how they are counseled, and most of the places where they want to use them most is NOT listening in a quiet environment.

Perhaps such a training schedule was required in the past because hearing aids were not as sophisticated in amplifying sound as today. However, it is doubtful that the “listening in quiet” setting of today is intended to facilitate an amplified listening schedule. So, if not, what is its purpose for listening in quiet?

Really, For Listening in Quiet?

This is doubtful. Many individuals, when in a quiet environment, do not wear their hearing aids. For some, wearing aids in quiet is unnecessary, and perhaps even unwelcomed. They can often communicate well in a quiet location, and if listening to the TV, simple turn up the volume to suit their needs. This is easier that putting on hearing aids. This is especially true for individuals with mild, moderate, and even some moderately-severe hearing levels. Realistically, most hearing-impaired individuals want amplification to help them in more complex listening environments than encountered in quiet.

With this background, the question to be asked is, why is a hearing aid programmed for listening in quiet? Is that what it is really for? If that is the thinking behind such a setting, perhaps this thinking might be revisited.

What is a Quiet Listening Environment?

How is a quiet listening environment described? Is this suggested to be a “quiet” home or office? If so, how “quiet” are these “quiet” locations? What is an acceptable noise level for an environment to be considered “quiet?”

Table 1 provides Equivalent Sound Level – Leq that quantifies a noise environment to a single value of sound level for any desired duration. This descriptor correlates well with the effects of noise on people. Leq is also sometimes known as Average Sound Level – LAT. Table 1 provides some measured noise levels of various locations around the home and other locations, and the maximum acceptable equivalent sound levels. The maximum levels are in the 50 dB range. How do these levels compare with sound levels found in the home? Typical home sound levels (in dB SPL) are shown in Table 2. Most of the sounds in Table 2 exceed the maximum acceptable sound levels as suggested by Table 1, especially when compared to the “living area” category. If that is the case, what is the purpose of “listening in quiet”, when even a quiet home is not really “quiet”? If background noise in a quiet home is a problem, then perhaps it should be managed via some form of noise management hearing aid program. In essence, listening in noise.

Table 1. This table provides some measured noise levels of various locations around the home, and the maximum acceptable equivalent sound levels. The maximum levels are in the 50 dB range. From: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/decibel-dba-levels-d_728.html.

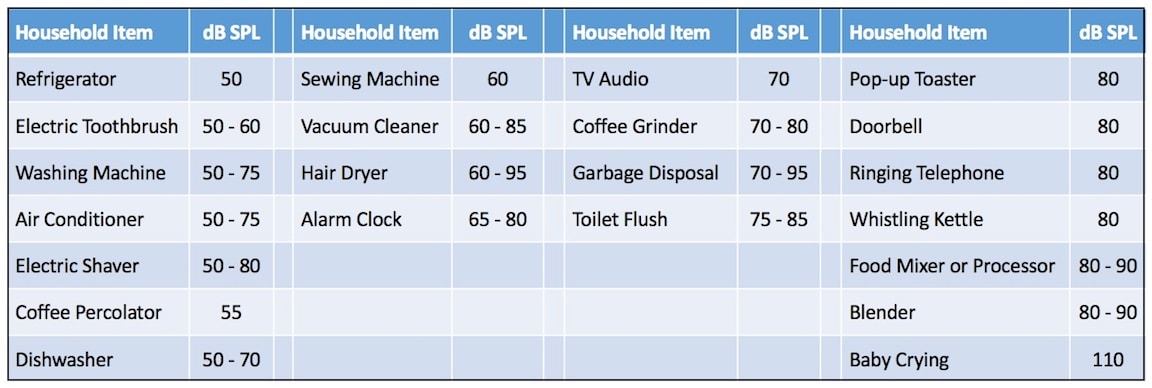

Table 2. Common household items/events and the SPL levels in dB associated with them. (Redrawn and modified from Center for Hearing and Communication). https://chchearing.org/noise/common-environmental-noise-levels/.

An office environment has often been identified as being “quiet,” and as such, would be expected to use the “listening in quiet” environmental hearing aid setting. However, this would depend greatly on what type of work environment was involved. Typical noise levels at work are shown in Table 3. Again, these do not appear to be sound pressure levels associated with a “quiet” environment since most of the office conditions equal and/or exceed the recommended maximum acceptable noise level.

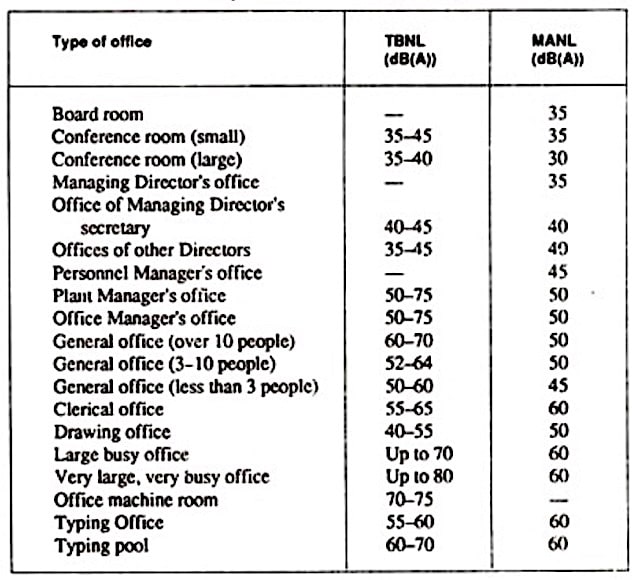

Table 3. Typical background noise level (TBNL) and recommended maximum acceptable noise level (MANL) for various offices. https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/noise-pollution/office-noise-sources-and-control-noise-pollution/84385/.

Generally, an acceptable noise level is the highest level of background noise that a listener is willing to tolerate while listening to running speech. If normal conversational speech is considered to be 65 dB SPL, then it would appear that many household sounds have at least a signal-to-noise ratio that is negative. The question remains, however, is what impact do these levels have as background noises such that they could/would render amplified communication unacceptable because they are too annoying? What is the level of noise to the level of target speech before the difference between the two is acceptable to a person wearing hearing aids?

It is known that an acceptable noise level (ANL) is independent of degree of hearing loss, so that factor is taken from the equation8. Acceptance depends, however, on the type of background noise (music vs. multi-talker, etc.). An in-depth discussion of ANL as a test protocol is not the intent of this post. A good discussion is presented by Recker9.

ANL (Acceptable Noise Level)

Tests exist to measure an ANL. In ANL tests, the highest background noise level a listener deems acceptable while listening to speech at their most comfortable level (MCL) is measured. To begin, the listener adjusts recorded running speech to their MCL through a modified method of adjustments. Next, a multi-talker babble (or other competing noise) is added to the speech. The listener adjusts the competing noise to the highest level that enables them to follow the speech passage without becoming tense or tired, in other words, to the highest level that they are willing to “put up with”. This determines the background noise level (BNL)10. As an example, if the MCL is 75 and the BNL is 70, the ANL would be 5 dB. Some might call this a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which would be correct, but the term “level” was appropriated to this in order to differentiate it from other SNR tests of speech recognition.

ANL Scores and Successful Hearing Aid Expectations

The higher the number, the worse the acceptable noise level is for the listener. In other words, those who report small ANL level scores are more likely to be successful hearing aid users. And, those who report large ANL level scores are less likely to be successful hearing aid users11,12,13,14.

General interpretation of the ANL score for successful hearing aid use is as follows13:

- ANL Score of 7 dB or less – Great prognosis for regular hearing aid use and acceptance.

- ANL Score of 8-12 dB – These scores are much more common and patients have a good (8) or bad (12) prognosis for regular and acceptable hearing aid use. Noise reduction technologies and greater counseling are suggested.

- ANL Score of 13 dB or greater – Expect to spend much time in counseling.

Plyler reported than in the 25 years of research at his laboratory, ANL values ranged from -2 to 29 dB in listeners with impaired hearing10, and Nabelek, et. al. found the most frequently observed ANL value to be around 10 dB for normal and hearing impaired subjects14. ANL results from various studies from Plyler’s lab are provided in Table 4, showing that score results were recorded often in excess of 10. Various reasons have been suggested for the wide range in scores reported in Table 1 and elsewhere, but these are beyond the scope of this post.

Table 4. ANL (acceptable noise levels) results from Dr. Plyer’s laboratory utilizing participants from a typical clinical caseload.

Based on the score results from Plyer’s lab, it would appear that most individuals might have trouble when using a HA in the presence of noise (ANL level scores greater than 8).

Question

So, because hearing aids are worn essentially in a noisy environment, why not program all aids for listening in noise rather than for listening in quiet? It is unclear what listening in quiet is intended to accomplish.

This is not a new concept, but perhaps expressed more overtly. For example, although research has routinely shown that hearing aids improve speech perception, neither speech perception scores in quiet or in background noise appear to impact hearing aid use – certainly not to the extent expected16,17. Additionally, Nabelek questioned if an individual’s willingness to listen in background noise might be more indicative of hearing aid use than actual speech understanding11. In other words, the use of hearing aids appeared to be related more to the acceptance of background noise than to speech understanding in quiet or in noise.

It has been documented also, that one of the first common complaints of hearing aid users relates to their inability to hear in background noise,18,19 not to listening in quiet. And, since essentially all amplified listening is in a noise environment, why not program hearing aids initially to function best in that environment? Make that the number 1 setting of the environmental listening settings?

Listening in Noise

Realistically, hearing aids are used mostly in a noisy environment – either background noise or in competing noise situations (multiple people talking in the presence of other competing sounds/noises). If this is the case, then a reasonable question to ask is: why is listening in quiet the primary designation as the number 1 environment listening setting? Shouldn’t it really be “listening in noise,” especially when noise is essentially impossible to avoid?

Explanations should be readily presented for programming a hearing aid’s number one setting to listening in quiet. A convincing explanation would be welcome, especially when the majority of hearing aid wearers do not change from one environmental listening setting to another, meaning that many listen in all environments to the “speech in quiet” setting. A common complaint if they move to a “listening in noise” setting is that the volume is no longer great enough.

Therefore, it is tempting to set the number 1 setting that individuals use to listening in noise. If the signal is not loud enough in some environments, then allow the user to adjust the gain upward until it is acceptable, or then to move to the “speech in quiet” setting, which generally provides greater overall loudness. The first suggestion requires a hearing aid with a user-adjustable volume control. But, why not? Such control is high on the demand list of hearing aid wearers as reported previously here on the HHTM site. Read about this in Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 related to user-adjustable volume control on hearing aids.

References

- Festen J. (1987). Explorations on the difference in SRT between a stationary noise masker and an interfering speaker. Acoust. Soc. Am., 82 (1987), p. S4.

- Glasberg BR, Moore BCJ. (1989). Psychoacoustic abilities of subjects with unilateral and bilateral cochlear hearing impairments and their relationship to the ability to understand speech. Audiol., 32 (1989), pp. 1-25.

- Festen JM, Plomp R. (1990). Effects of fluctuating noise and interfering speech on the speech-reception threshold for impaired and normal hearing. Acoust. Soc. Am., 88 (1990), pp. 1725-1736.

- Plomp R. (1994). Noise, amplification, and compression: considerations of three main issues in hearing aid design. Ear Hear., 15 (1994), pp. 2-12.

- Festen JM. (1993). Contributions of co-modulation masking release and temporal resolution to the speech-reception threshold masked by an interfering voice. Acoust. Soc. Am., 94 (1993), pp. 1295-1300.

- Moore BCJ. (1995). Perceptual consequences of cochlear damage. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Grant JW, Walden TC. (2013). Understanding excessive SNR loss in hearing- impaired listeners. Am. Acad. Audiol., 24 (2013), pp. 258-273.

- Nabelek AK, Tucker FM, & Letowski TR. (1991). Toleration of background noises: Relationship with patterns of hearing aid use by elderly persons. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34, 679-685.

- Recker K. (2015). Acceptable noise levels: a useful tool. Audiology Online, January 20, 2015.

- Plyler, P. (2015, June). 20Q: Acceptable Noise Level Test – The basics and beyond. AudiologyOnline, Article 14403. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.

- Nabelek A, Tucker F, & Letowski T. (1991). Toleration of background noises: Relationship with patterns of hearing aid use by elderly persons.Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34,679-685.

- Lytle S. (1994). A comparison of amplification efficacy and toleration of background noise in hearing impaired elderly persons. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

- Nabelek A, Freyaldenhoven M, Tampas J, & Burchfield S. (2006). Acceptable noise level as a predictor of hearing aid use.Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 17(9), 626-639.

- Freyhaldenhoven M, Plyler P, Thelin J, & Burchfield S. (2006). Acceptance of noise for monaural and binaural hearing aid fittings. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 17, 659–666.

- Nabelek A, Tampas J, & Burchfield S. (2004) Comparison of speech perception in background noise with acceptance of background in aided and unaided conditions.Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 47,1001-1011.

- Bentler R, Niebuhr J, Getta C, & Anderson C. (1993). Longitudinal study of hearing aid effectiveness. II: Subjective measures.Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 820-831.

- Humes L, Halling D, & Coughlin M. (1996). Reliability and stability of various hearing aid outcome measures in a group of elderly hearing aid wearers.Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 39,923-935.

- Kochkin S. (2002a). 10-year customer satisfaction trends in the US hearing instrument market.Hearing Review, 9(10), 14-46.

- Kochkin S. (2002b). Consumers rate improvements sought in hearing instruments. Hearing Review, 9(11),18-22.

That’s one of the most thought-provoking and interesting articles I’ve read in a long time. It also reinforces the view that an ANL test should be much more routinely undertaken and should be more widely understood that it contributes different but very useful information compared to tests of speech understanding in noise.