HHTM Staff

HHTM Readers: drug regimens for prevention and/or treatment of malaria were the topics for the last two series posts, following a post on the disease itself. The disease is terrible and so are the handful of drugs used to prevent or treat it. Quinine is the standout – historically, politically, economically, audiologically, and sometimes fatally. It’s such an interesting drug that this post had to be cut in two. Here’s Part 1 of the Quinine Story and Part 4 in the Malaria series.

Quick Summary of Malaria and Antimalarials

In addition to the enormous disease burden in endemic countries, malaria is on the rise as world travel to exotic locations increases. Unlike so many other diseases of the past that were world scourges (e.g., small pox, polio, yellow fever), there is no simple shot, sugar cube or skin vaccine to ward off the disease. Preventive drug treatment regimes are recommended, but they all have challenging medication schedules which makes compliance difficult and low. In addition, they all have serious side effects, and varying effectiveness. The same problems apply when the same drugs or new drugs are used to treat those who contract the disease. Regular doses of antimalarial drugs can have long-term side effects, including liver and kidney damage and hearing loss which may or may not be reversible. Even though the drugs cure the disease (i.e., eliminate the parasite from your body), immunity is weak and fleeting: close proximity to the disease (e.g., being born and raised in the endemic country and surviving childhood malaria) confers some immunity. For others, it is more than possible to get malaria multiple times and experience adverse treatment effects each time.

The Audiology Connection: Despite centuries of devastation wreaked by malaria and antimalarial treatments, there is little understanding of whether malaria itself affects hearing and, if so, how. Although antimalarial treatments are well documented as “causes” of hearing loss, there is little understanding of how or why the various treatments affect the human auditory/vestibular system. Perhaps because the disease, left untreated, devastates and kills, there has been little or no attempt to determine whether the ototoxicity is caused by treatment or disease.

Quinine’s Fascinating History

No one would undertake to bring into England a medicine coming from the Spanish colonies, sponsored by the Vatican, and known by the abhorrent name of the Jesuits’ powder. (Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England, 17th century)

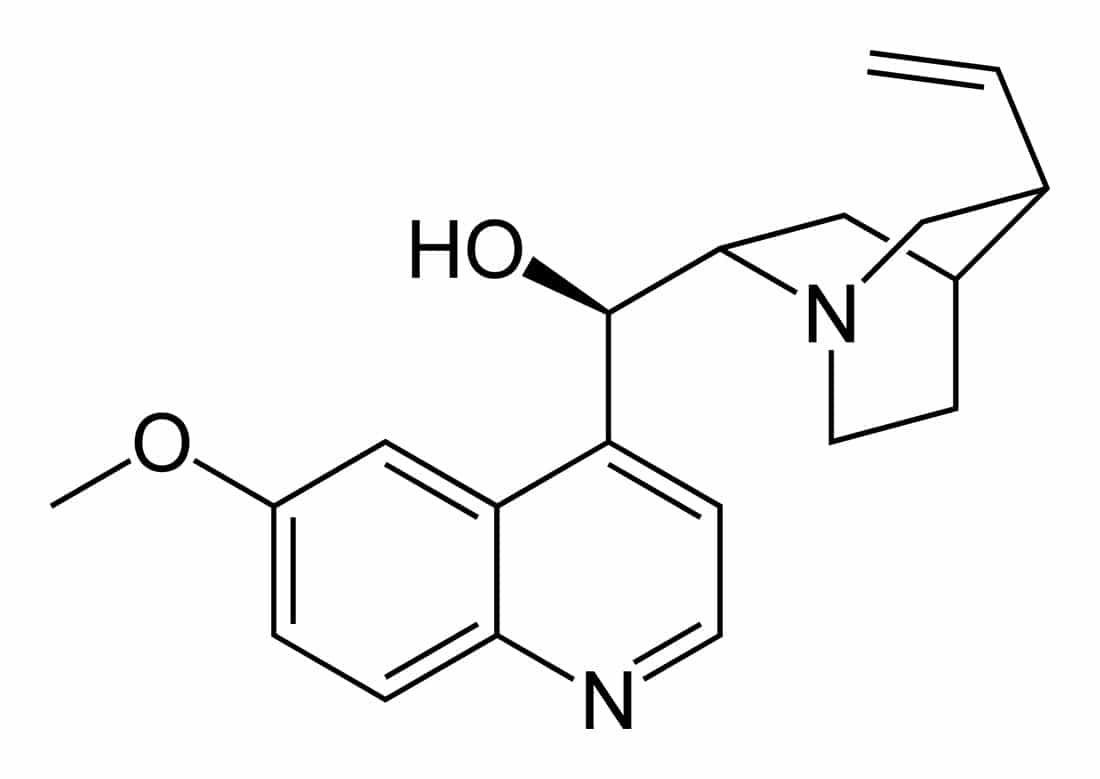

This is the granddaddy drug for treating malaria. It’s also the familiar bitter taste we know from tonic water, where it is present in trace amounts. Quinine was first discovered in the 1600s by Jesuit missionaries in Peru who observed the indigenous population’s habit of making tonic water by stripping and brewing bark from chinchona trees, then ingesting the bitter “tea” (they sweetened it) to reduce shivering in cold weather. It seems malaria did not exist in the New World at that time.

Interesting to read this article about quinine and the effects on the inner ear.

In 1984 I was travelling to Nepal and India, and a Doctor from a Tropical Disease clinic in Toronto prescribed this drug for me. Luckily I had an allergic reaction to it after a month and stopped taking it. Upon returning to Canada a year later, I noticed my hearing loss which had already begun diminishing 5 years before I left on this trip at age 25 due to sensorineural hearing loss, had greatly diminished. I then learned about this quinine/hearing loss connection. Important information!