Wow! Is That Hair in Your Ears?

This discussion is not about the hairs (cilia) of the cochlea, where acoustic energy is translated into electrical energy, but about ear hair. You know, the hairy ear growth that one sometimes notices in a person’s ears, but almost never says anything about – as if talking about it were taboo. You can talk about it behind one’s back, but never to their face!

There are many jokes made about men having little or no hair on their head, but when is the last time you heard anyone say, “Wow, you have really hairy ears,” unless they have been beyond their third martini.

This post is actually a continuation of the current series (Parts 1,2, and 3) relating to the human ear canal and earwax. What does ear hair have to do with earwax? As will be discussed in this, and in later posts, it can have an impact on preventing earwax from being released naturally from the ear canal.

This post is not intended to offer suggestions on how to comment gracefully (if even possible) on one’s ear hairs. This may not be one of the most pleasant topics, but is something that hearing professionals should be able to address.

Where Do Ear Hairs Fall Histologically?

From an histology viewpoint (Perry and Shelly, 1955), the ear canal skin has three appendages (derivatives):

- Ceruminous glands

- Sebaceous glands

- Hairs

Last week’s post concentrated on the ceruminous and sebaceous glands in the ear canal skin. In both cases, each empties into the outer portion of the ear canal through hair follicles.

This week the focus is on the ear hair itself, hair arising from follicular cartilage of the outer cartilaginous portion of the ear canal or from the tragus, antitragus, or helix portions of the auricle/pinna.

Ear Hair

The hairs that can be found in and around the ear fall into two different categories:

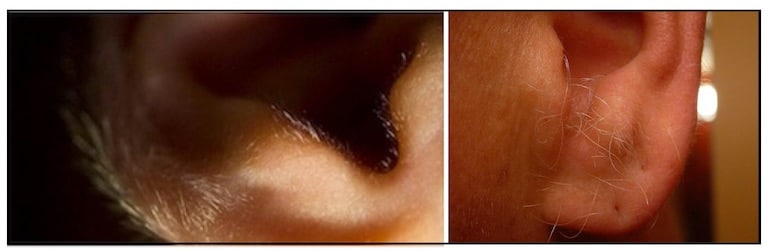

- Vellus hair – tiny, short, thin, and almost invisible (Figure 1 left image) that grow in most places on the human body. At the ear, they are present in the very outer portion of the ear canal (in the outer cartilaginous area or on the pinna itself). The density varies among individuals. When short, it is often referred to as “peach fuzz.” Strands are usually short (less than 2 mm), and the follicle is not connected to a sebaceous gland (Marks and Miller, 2006). Marks and Miller also identify other cases of irregular vellus hair growth as shown in Figure 1 right image, with such hairs growing to as long as 20-40 mm.

Vellus hair is mostly non-pigmented. However, during and after puberty, dihyrotestosterone (DHT) present in the body causes vellus hairs on the arms, legs, faces, and in other parts of the body to grow thicker and darker, into “terminal” hair – to a greater extent in men than women (Jackson and Nesbitt, 2012). With aging, the normal growth cycles of hair (growth, resting, and falling out phases) get out of whack, and as a result, some hairs grow longer before they are shed.

Figure 1. Short vellum hairs (left image) and long vellum hairs (right image) on the tragus, antitragus, and helix. Note the lack of hair pigmentation.

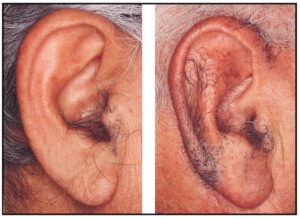

- Tragi hairs – larger/thicker stiff terminal. They take their name from Latin (tragos ‘goat’) with reference to the characteristic tuft of hair that is often present, likened to a goat’s beard. These can be prominent in the outer portion of the ear canal, on the tragus, antitragus, and in extreme cases over the helix (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Tragi hairs found in the tragus, antitragus, and helix portions of the ear canal (Hawke and McCombe, 1955).

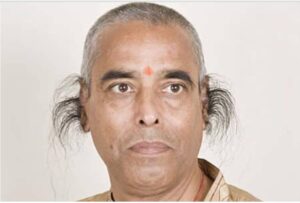

Tragi hairs can be numerous in some people and also very prominent. This condition is more often found in men than women. In some extreme cases, the ear hair can be quite long, recorded as being 5.2 inches by the Guinness World Records in 2003 (Figure 3) for Radhakant Baijpai. Since then, the 64 year-old (in 2015) grocer’s ear hair has continued to grow, being almost 10 inches long in 2009. He said that he has no intention to cut it, having been growing since he was 18 years old.

Figure 3. The world’s record length for ear hair is held by Radhakant Baijpai, an Indian grocer. The last recorded measurement was almost 10 inches long. (Photo from Weirdlife).

Hair Growth in the Ear Canal

Ear hair is generally identified as the terminal hair developing from the follicles inside the ear canal. However, in its broader sense, ear hair may include the fine vellus hair covering much of the ear (particularly at the prominent parts of the anterior ear), as well as the terminal, or tragi hair.

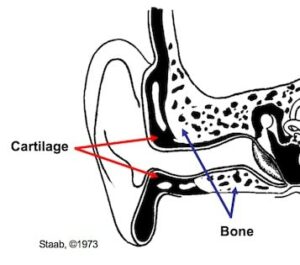

Figure 4. General drawing of the ear canal (external auditory meatus) showing the areas lined by cartilage and bone.

Hair growth within the ear canal itself is limited to the cartilaginous ear canal – roughly the outer 1/3 of the ear canal (Figure 4). The inner 2/3 of the ear canal, called the bony ear canal, does not have sufficient dermis and hypodermis underlying the epidermis to support the hair root in the hair follicle. Therefore, ear hair is not found in the deeper (bony) structure of the ear canal. Hair growth within the outer portion of the ear canal seems to increase and become stiffer as men age (along with an increase in nasal hair growth).

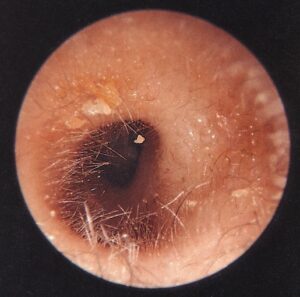

Figure 5. Ear hair growing just inside the opening of the ear canal (otoscopic photograph). (Hawke & McCombe, 1955). The light from the light source gives the impression that these are non-pigmented hairs, but they are not.

A more traditional length and location of tragi (terminal) hair just inside the ear canal opening is shown in the photo of Figure 5, taken from a video otoscope.

Ear Hair Function

Ear hair serves a protective function by filtering dust from the air and also acts to impede the entry of insects and other debris. It has been reported as well that heavy growth may prevent hearing aids from making a good seal, when needed (the topic of an upcoming post). Heavy tragi hair can sometimes create problems when making ear impressions, and often “barbering” is required because certain ear impression materials might allow the hairs to become embedded into the ear impression, potentially causing some discomfort when removing the ear impression with hair attached.

As in the left side of Fig. 2, similar thick hairs are often found lining the outer portion of the ear canal and can interfere with the normal outward migration of wax and debris, leading to an accumulation in the ear canal. The right side of Figure 2 shows hairs throughout the auricle, and can cover the ear in excess of that shown here. This condition is reserved for males only and is inherited as a Y-linked trait (Hawke and McCombe, 1955).

The accumulation and management of earwax, and the impact of hearing aids on earwax, will be the subject of a future posts.

References

Hawke M., and McCombe, A. (1955). Diseases of the Ear, a Pocket Atlas, Manticore Communications, Inc., Hamilton, Ontario, CA.

Jackson, Scott; Nesbitt, Lee T. (April 25, 2012). Differential Diagnosis for the Dermatologist. Springer Science & Business Media.

Marks, James G; Miller, Jeffery (2006). Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology (4th ed.). Elsevier Inc.

Wayne Staab, PhD, is an internationally recognized authority in hearing aids. As President of Dr. Wayne J. Staab and Associates, he is engaged in consulting, research, development, manufacturing, education, and marketing projects related to hearing. His professional career has included University teaching, hearing clinic work, hearing aid company management and sales, and extensive work with engineering in developing and bringing new technology and products to the discipline of hearing. This varied background allows him to couple manufacturing and business with the science of acoustics to bring innovative developments and insights to our discipline. Dr. Staab has authored numerous books, chapters, and articles related to hearing aids and their fitting, and is an internationally-requested presenter. He is a past President and past Executive Director of the American Auditory Society and a retired Fellow of the International Collegium of Rehabilitative Audiology.

**this piece has been updated for clarity. It originally published on May 3, 2016