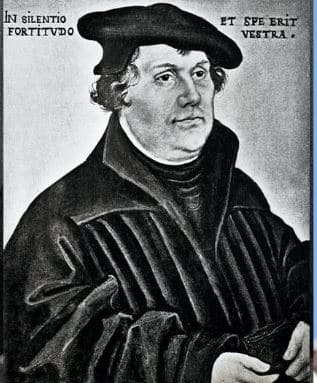

Martin Luther, renowned as the Father of Protestantism, played a pivotal role in shaping the modern world by famously breaking away from the Catholic Church. As a simple German monk hailing from a peasant background, Luther’s influence was immense. His extraordinary conviction, determination, and boldness made him a puzzling yet intriguing figure. Few individuals in history have generated as many captivating stories, both positive and negative, as Martin Luther.

While he witnessed his teachings being implemented by many and served as the inspiration behind Lutheranism, the first of the numerous Protestant faiths that exist today, he was also known for his volatile nature and occasional irrationality.

Could these erratic behaviors be attributed to conditions like endolymphatic hydrops or Meniere’s Disease?

Early Life of Martin Luther – Hans and Margarethe Luther

Martin Luther, born in 1483, was the eldest son of Hans and Margarethe Luder, who later changed their surname to Luther. They resided in Eisleben, now part of Germany. Luther’s childhood was challenging and left a lasting impact on him. Hans and Margarethe adopted extremely harsh methods of child rearing, with records indicating that Luther suffered severe nosebleeds as a result of their beatings. Psychologists today speculate that Luther’s tumultuous childhood might have contributed to his revolutionary ideas. In 1484, the family relocated to Mansfeld, where his father held a lease on copper mines and smelters and served as one of the citizen representatives on the local council. Luther’s mother, described as a hard-working woman from trading-class stock with modest means by religious scholar Martin Marty, worked tirelessly to support her family. Hans had ambitious aspirations for himself and his kin, particularly his eldest son, whom he hoped would become a lawyer.

Young Martin’s educational journey began in Latin schools in Mansfeld. He subsequently attended Magdeburg in 1497, a school operated by the Brethren of the Common Life, a lay group. In 1498, he moved to Eisenach. These three schools emphasized the “trivium,” comprising grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Luther later likened his education in these institutions to purgatory and hell, as these were arduous years for him. During this period, he started devoting himself to religious activities. Following a near-death experience during a terrifying thunderstorm, Luther resolved to align his life more closely with God’s teachings. Consequently, he abandoned his college education and abandoned his plans to study law. At the age of 24, he entered the Augustine friars’ monastery and was ordained as a priest in 1507.

The Reformation and Luther’s 95 Theses

While Luther remained deeply Catholic, he vehemently disagreed with several practices of the early Church. These included immoral behavior, inadequate education of clerics, and the absenteeism of Bishops from their assigned parishes. His discontent with the Church’s practices ultimately led to the Protestant Reformation.

While Luther remained deeply Catholic, he vehemently disagreed with several practices of the early Church. These included immoral behavior, inadequate education of clerics, and the absenteeism of Bishops from their assigned parishes. His discontent with the Church’s practices ultimately led to the Protestant Reformation.

Between 1520 and 1530, Luther developed the fundamental principles of his new faith. His beliefs diverged significantly from the teachings of the Catholic Church and revolved around four major articles. His primary assertions were as follows:

- Man is saved by faith alone (“sola fide”).

- The Bible is the sole source of authority in the church (“sola scriptura”).

- The church comprises the entire Christian community.

- All vocations have equal merit, and individuals should serve God according to their individual callings.

Luther’s open challenge to the Catholic Church brought both chaos and unity to the masses. His “95 Theses” served as the catalyst for the Reformation, which eventually led to the enlightenment. Interestingly, Luther himself believed that the devil resided within his own body at times.

Luther’s Battle with Meniere’s Disease

Throughout his life, Luther suffered from severe constipation, and it is documented that he experienced his greatest enlightenment while sitting on the toilet. His ailments were well-documented, as he openly discussed them in his letters, and his friends provided reports attesting to their veracity. Most of his diseases, such as bladder stones, chronic constipation, and hemorrhoids, were common and widely known to 16th-century physicians.

The first documented Meniere’s attack afflicted Luther on July 6, 1527, when he was 43 years old. The episode commenced with a roaring tinnitus in his left ear, which escalated dramatically and seemed to engulf the left half of his head. This was followed by a period of sickness and collapse, although Luther remained conscious throughout. The symptoms subsided, except for the persistent tinnitus, which persisted for the remainder of his life, albeit with varying intensity.

Luther experienced similar attacks at irregular intervals, characterized by intensifying tinnitus and vertigo, causing significant distress. Past investigations into Luther’s diseases interpreted these attacks as manifestations of a psychiatric disorder and chronic inflammation of the middle ear. One study even posits that Luther’s case was a typical manifestation of Meniere’s disease in his left ear, occurring more than three centuries before Meniere’s classical observation.

Luther experienced similar attacks at irregular intervals, characterized by intensifying tinnitus and vertigo, causing significant distress. Past investigations into Luther’s diseases interpreted these attacks as manifestations of a psychiatric disorder and chronic inflammation of the middle ear. One study even posits that Luther’s case was a typical manifestation of Meniere’s disease in his left ear, occurring more than three centuries before Meniere’s classical observation.

Luther described feeling as if the devil would whistle and roar in his ears and squeeze his heart. At times, the spinning sensation in his head was so intense that he would fall out of his chair. He regarded his severe tinnitus as a Satanic affliction, writing, “When I try to work, my head becomes filled with all sorts of whizzing, buzzing, thundering noises.” The condition became so severe that he even hired a bodyguard to prevent him from physically harming others during excruciating bouts of tinnitus. Modern physicians speculate that Luther may have suffered from Meniere’s disease, an inner ear disorder that causes severe balance problems. Some also suggest that his Meniere’s disease and hallucinations could have been a result of syphilis, which was rampant in Europe during that time.

By 1529, Luther’s ailments had taken a toll on his demeanor, writings, and speeches. In particular, his views on Jews changed drastically from defending them as “God’s people whom the Lord will redeem in time” to expressing abhorrent sentiments about the Jews of his day. It is possible that if Luther had access to treatment for his tinnitus, his volatility could have been mitigated. In 1541, he became deaf after experiencing severe earaches and a discharge from his ears. He also suffered from extremely high blood pressure, which led to angina pectoris, a heart disease causing chest pain spasms. Eventually, his diseased heart failed, and he lost consciousness. As his friends shouted questions into his deaf ears, wanting to know if his faith in Christ remained steadfast as he approached the end, Luther’s final word in response was a resounding “yes.”

On February 18, 1546, Martin Luther passed away.

About the author

Robert M. Traynor, Ed.D., is a hearing industry consultant, trainer, professor, conference speaker, practice manager and author. He has decades of experience teaching courses and training clinicians within the field of audiology with specific emphasis in hearing and tinnitus rehabilitation. He serves as Adjunct Faculty in Audiology at the University of Florida, University of Northern Colorado, University of Colorado and The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

**this piece has been updated for clarity. It originally published on October 7, 2014