Hearing Aid Evolution – A Ride Through History

Last week’s post was the second of what has now become a five-part series on the “Evolution of Hearing Aid Technology and Techniques – A Ride Through History.” The first week focused on factors that drive hearing aid development, and then highlighted some of the major developments (primarily hardware) that shaped the changes to hearing aid design. The second post took the ride from power supplies through developments related to hearing aid transducers. This post will review changes that relate more to developments related to fitting issues.

Hearing Aid Configurations

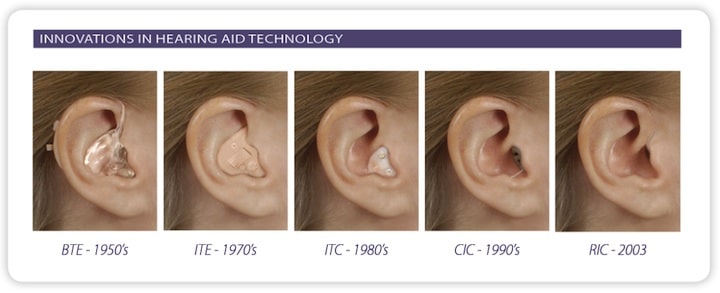

Body-worn units made hearing aids practical, and ear-level instruments expanded the market. And, even though ear-level hearing aids in various forms (BTE and those in the canal) dominate the market today and generally have similar functions, certain developments helped expand the market. The following illustration documents the major cosmetic changes in ear level hearing aids from the 1950s.

Major innovative cosmetic changes in hearing aids since the 1950s that dominated the marketplace. The BTE (behind-the-ear) hearing aid of the 1950s is shown with a full-shell earmold. In the 1970s, the ITE (in-the-ear) began its steady climb to drive the market. Smaller hearing aid components led to less visible (more cosmetic) hearing aids during the 1980s with the ITC (in-the-canal) hearing aid being a featured configuration. This was replaced in the 1990s with the CIC (completely-in-the-canal) unit, again benefiting from instrument component size reductions. The RIC (receiver-in-the-canal) of the 2000s and continuing today benefited from component size reduction, but also allowed a larger processor (behind the ear) to allow for electronic and acoustic benefits. Courtesy of SeboTek.

More Specific Developments That Influenced Hearing Aid Products

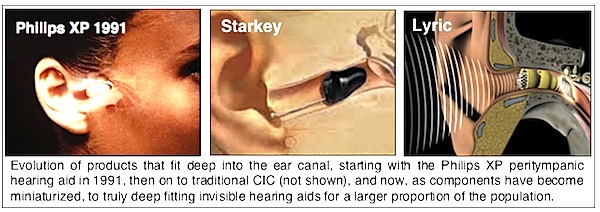

- Deep Canal Hearing Aids – Philips Hearing Instruments introduced the XP Peritympanic hearing aid in 1991{{1}}[[1]] Staab, W.J. The Peritympanic instrument: fitting rationale and test results. The Hearing Journal, 45, No. 10, pp 21-26, October 1992[[1]]. This was the first hearing aid designed where all the electronics were designed to fit deeply in the ear canal, and not be visible.

- CIC Hearing Aids – Completely-in-the-canal hearing aids directly resulted from the interest in deep canal hearing aids, especially arising from the timidity and difficulty of many individuals to take deep impressions. It was also difficult to position all of the hearing aid components deeply in the ear canal, leaving a large population that was unserved with the deep canal product. As a result, CIC instruments were made with less visibility in the concha, but without deep termination and acoustical advantages of a deeply seated speaker/receiver.

- MIC/IIC Hearing Aids – Micro-in-the-canal (MIC), and Invisible-in-the-canal (IIC) hearing aids have been a natural development resulting from continued miniaturization of hearing aid components, especially the microphone, speaker, and ICs. The same can be said relative to extended wear hearing aids. The latter should be no surprise because the eyeglass industry had already opened that door, and the hearing aid industry has a tendency to follow other disciplines in its product use, whenever it can.

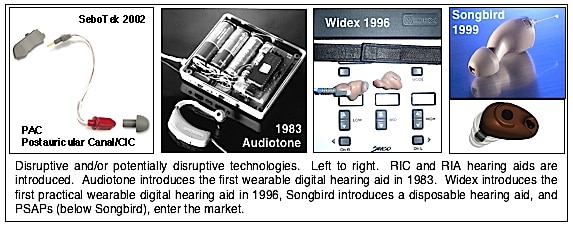

- Hybrid Hearing Aids – These are hearing aid developments that sometimes have, or had the potential, to be disruptive to the industry. Disruptive technology is one that creates a new market and value network, and eventually disrupts an existing market and value network. While a disruptive innovation often takes a few years or decades to displace an earlier technology, the digital hearing aid, and the RIC (called the PAC initially – Post Auricle Canal) by SeboTek, the patent holder and introduced in 2003{{2}}[[2]] PAC: Post-Auricular Canal. American Academy of Audiology, San Antonio, TX, April 2003[[2]] had immediate transitional impacts.

- RIC/RIA Hearing Aids – Receiver-in-the canal and receiver-in-the-aid hearing aids (SeboTek, 2003) have

unquestionably been disruptive technologies, taking traditional BTE (behind-the-ear) hearing aids from about 15% at the time they were introduced to approximately 50% of all hearing aids sold today. Expanding on this technology, MIC (microphone-in-concha) hearing aids evolved.

unquestionably been disruptive technologies, taking traditional BTE (behind-the-ear) hearing aids from about 15% at the time they were introduced to approximately 50% of all hearing aids sold today. Expanding on this technology, MIC (microphone-in-concha) hearing aids evolved. - Analog to Digital Signal Processing – The first wearable digital hearing aid was introduced in 1983 {{3}}[[3]] Nunley, J., Staab, W.J., Steadman, J., Spencer, B., Wechsler, P., Egolf, D., & Brechbiel, R. A Wearable Digital Hearing Aid, The Hearing Journal, Vol. 36, No. 10, October, 1983, pp. 29-31, 34-35[[3]], and the first commercially successful all digital hearing aid was created by Widex in 1996. Today, with substantial improvements, essentially all hearing aids use digital signal processing, or are considered digital hearing aids. This was definitely a disruptive technology

- Disposable Hearing Aids – The Songbird disposable hearing aid proved that completely different hearing aid concepts could exist from traditional designs and uses{{4}}[[4]] Staab, W.J., Sjursen, W., Preves, D., and Squeglia, T. A one-size disposable hearing aid is introduced. The Hearing Journal, Vol. 53, No. 4, April 2000 pp 36, 38-39, 40[[4]]. It did not become a disruptive technology, primarily due to the fit of the instrument. It might have been an entirely different story if later available smaller sized components had been available, because the sound quality equaled or bettered premium hearing aids of the day{{5}}[[5]] Moore, Brian C.J., Stone, M.A., and Alcántara, Technical Review of the Songbird Disposable Hearing Aid, Commissioned by Defeating Deafness, January, 2001[[5]].

- PSAPs – Personal Sound Amplification Products. These are products that allow the user to pick up sounds for specific purposes – such as listening to bird calls, etc. These are not regulated by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), and are not considered hearing aids{{6}}[[6]] Guidance for industry and FDA staff. Regulatory Requirements for Hearing Aid Devices and Personal Sound Amplification Products, Document issued on: February 25, 2009, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Ear, Nose, and Throat Devices Branch, Division of Ophthalmic, Neurological and Ear, Nose, and Throat Devices Office of Device Evaluation[[6]]. Could these end up being disruptive technology? Only time will tell.

- RIC/RIA Hearing Aids – Receiver-in-the canal and receiver-in-the-aid hearing aids (SeboTek, 2003) have

Other Hearing Aid Significant Developments

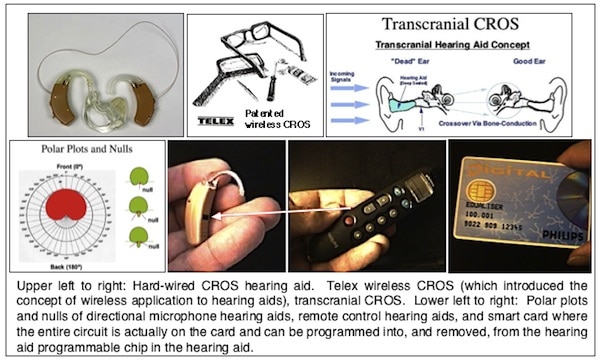

- CROS and Variations – These were introduced with traditional wired application in 1965, but then as a wireless device (TeleCROS by Telex, 1975). A later development related to single-sided deafness is the transcranial hearing aid concept where sound (either air-conducted or bone-conducted amplified sound) is directed to the non-functional ear, with the signal then being picked up by the good ear due to essentially 0 dB interaural attenuation bone-conduction transmission.

- Directional Microphone Hearing Aids – Directional microphone hearing aids were introduced in about 1973, had an immediate impact, and then almost disappeared as other technologies evolved, primarily the custom-molded hearing aid products (ITE, ITC). With the massive growth in custom–molded products, and using the directional microphone design at the time, they could fit only a very limited number of ITE custom hearing aids. BTE hearing aids had dropped to about 15% use in the marketplace, and many of these were power instruments, not really designed for directional microphones. However, when dual, small, omnidirectional microphones could be used, and ICs and receivers became smaller, things changed. RIC and similar technology became popular, and software allowed the two omnidirectional microphones to function as a directional microphone. These collectively offered hearing aid designers an opportunity to work on a long-standing, and nagging issue – that of improving the signal-to-noise, which is something that directional polarity allowed.

- Remote Control and Wireless Communications – Many hearing aid users have difficulty managing the small controls on smaller current hearing aids. Remote control of the hearing aid function by the user has taken a number of directions: infrared, electro-magnetic induction, radio frequencies, and expect Bluetooth technology.

- Smart Cards – The use of smart cards was proposed as a transition from hardware-to software-control of hearing aids{{7}}[[7]]Staab, W.J., Preves, D., Yanz, J., Edmonds, J. Open platform DSP hearing instruments: a move toward software-controlled devices, The Hearing Review, December 1997, pp. 22-24, 27[[7]]. The smart card allowed software algorithms to change the performance of one hearing instrument into that of a completely different hearing instrument (not just to program the parameters of the chip within the hearing aid). Essentially, it allowed taking a hearing aid performance physically from the smart card and programming it to a universal chip in the hearing aid, and making the hearing aid a completely different unit. If the “new” hearing aid was not what was desired, the hearing aid could then be returned to the smart card. This was truly an open platform in its broadest sense.

- Remote Teleprogramming – This concept was introduced by Philips in 1977{{8}}[[8]]Staab, W., Edmonds, J, and Garcia, H. Remote Teleprogramming (RTP): Future directions to patient management, High Performance Hearing Solutions, Vol. 2: Marketing and Technology, Supplement to The Hearing Review, November, 1997, pp 5-52[[8]], involving an approach that allowed reprogramming of a hearing aid without face-to-face contact. Programming/reprogramming was performed acoustically, using the dual tone multiple frequencies of the common telephone. This action could be accomplished from any place in the world.