Today picks up on a series begun in response to a headline-grabbing proclamation by a manufacturing CEO:

“‘The hearing aid industry uses every new thing … to raise prices.”

To which Hearing Economics posed rhetorical questions and slowly began addressing them:

- What is the basis for making such a claim?

- Are claims like this true or do they just sound true?

- Does it matter whether they’re true or not, if they become accepted articles of faith in our collective conscious?

Are Hearing Aid Prices Going Up?

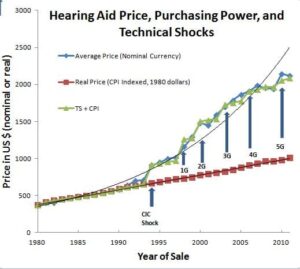

Answer #1: No. Today’s first-generation technologies–our “low end” product niche nowadays — cost $40 less in real dollars than traditional aids did in 1980. Adjusted for inflation, that $399 anchor price for entry-level instruments is far below the real dollar cost of hearings aids in 1980. (red box projections, Fig 1).

Answer #2: It depends. The range of Price has grown with every differentiation. The low end has held firm in the $300-400 nominal price range; the upper range has increased with advancing technologies.

Answer #3: Yes. Yes, major technological shocks come with price tags that manufacturers pass on to retailers and end users. The average Price of hearing aids began rising faster than inflation in 1994 when the first truly differentiated product entered the market. Over 18 years, premium pricing has added $59.70/year to average retail pricing (blue diamonds, Fig 1).

Figure 1 serves as the basis for answering the first two rhetorical questions. The CEO’s assertion that the “hearing aid industry” ties price to innovation has validity. But that only begs the question of who is taking the price increases along the supply chain.

Are Hearing Aid Manufacturers Price Villains?

Perhaps, but they may not be and they may not be acting alone in any case. As noted previously,

“Hearing Aid Price is still in the closet, but it’s being outed by professional and public outcry by squeezed Audiologists and consumers. If those two groups are outside picketing, who’s in the closet? Current conventional wisdom points to Machiavellian Manufacturing Monopolists. Before we jump on that bandwagon, let’s take a peek in the closet for verification.”

Manufacturers are well positioned at present to exercise monopolistic pricing, but they do not set retail prices to end users, which is all that Figure 1 can address. What about those “squeezed” Audiologists who are, after all, the final arbiters of retail pricing? What prices do they face at the wholesale level? What would Figure 1 look like if it were for wholesale rather than retail pricing?

Answering that set of questions requires knowledge of idiosyncratic wholesale pricing arrangements between manufacturers and providers (Audiologists and hearing aid aid dispensers). Such information is confidential and constantly in flux as both sides vie for a competitive edge.

Both sides of the equation are in constant, individualized negotiations to define their relationships/alliances in local markets. Providers negotiate lower invoice pricing and add-ons (e.g., extended warranty) as a means of reducing marginal costs and increasing marginal profits; manufacturers negotiate volume discounted pricing to various providers as a means of increasing local market share and building market power.

Hearing Economics Gets It For You Wholesale

Hearing Economics tried a number of schemes to construct a Wholesale price figure as a function of time. Getting individual practitioners to share actual dollar costs of product was not an option, as transparency is not a strength of our profession at present (more on that in a later post on unbundling).

But perhaps they would share their annual percentage change in invoice prices for different levels of technology. That didn’t pan out so well because individual practitioners either don’t track this metric regularly or they don’t want to share. In addition, different practitioners reflect their local markets as well as gravitating to preferred manufacturers and technology levels; thus, they are not representative of the general US market.

Besides, comparing percentage change across technology levels doesn’t make much sense: adding $50 to the low end marks a 12%-13% increase, but only a 3% increase for high end products.

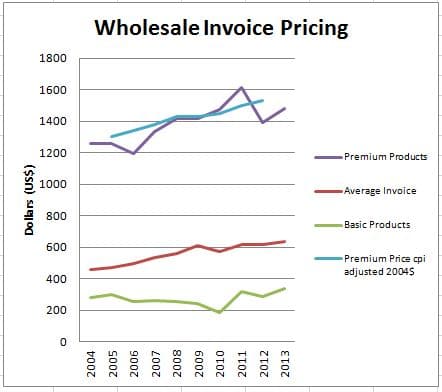

Instead, Hearing Economics appealed to large buying groups, which tend to negotiate annually with multiple manufacturers on behalf of diverse and large groups of individual providers. Hence, their numbers are more representative of the general market and they are better economic estimates of the manufacturers’ Willingness to Sell. The appeal paid off, at least back to 2004, and here is Figure 2 to prove it.

In-depth discussion of Figure 2 is deferred till next week, but here are a few thoughts that spring out right away:

- Wholesale pricing of premium products (purple line) did not rise faster than inflation (blue line) since 2004.

- Wholesale pricing of low-end products remains below $400. Period. The marginal cost of these aids denotes the lower limit of the Big 6’s Willingness to Sell, but it’s too high to account for the $399 aids we see advertised as an anchor price. Such instruments are likely coming from other sources.

- The average wholesale cost of product is well below premium products, consistent with one buying group’s estimate that premium product sales comprise about 1/3 of all hearing aid wholesale purchases, not much different from 2004/5 estimates.

If you redo Figure 1 for the period from 2004 on, you’ll find that retail average Price tracked inflation (2004$) very closely as well. To me, that means there aren’t any villains in this story; there are companies and people working hard to create useful innovation and sell it–wholesale or retail– at defensible prices to providers and consumers. On average, I don’t see any winners or losers here.

What about the cries from “squeezed” Audiologists? What about the cries from “gouged” consumers? Individually, they likely have validity as well and we’ll get to that in the next post or two.

(editor’s note: this is Part 6 in the multi-year Hearing Aid Pricing series. Click here for Part 5 or Part 7)