Should female wannabe Audiologists skip years of schooling and expensive AuD programs and go to work at Beltone instead? It’s an unacceptable question in polite Audiology society, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be asked. With AAA just around the corner, it seems like a good time to start this discussion. Oddly, my fellow editor David Kirkwood had thoughts about AAA and gender gaps this time last year. Must be Spring….

Why Bring This Up?

Consider some data from the broader field of healthcare. Female PCPs would have fared better economically by foregoing medical school and pursuing careers as Physicians Assistants (PAs). That’s the politically incorrect but data-driven conclusion of a thought-provoking study published last year by two Yale economists in the Journal of Human Capital.{{1}}[[1]]Chen MK & Chevalier JA. 2012. Are Women Overinvesting in Education? Evidence from the Medical Profession. J Human Capital, 6(2), pp 124-149. [[1]]

On the face of it, that’s unexpected. The education gap has closed over the last two decades–women and men are neck and neck these days in getting their BAs, MBAs, LLBs, and MDs. With such a big accomplishment under their belts, one would think women were on a career roll. But, even as women have gotten more and higher degrees, the past two decades have seen no decrease in the significant and persistent gender wage gap.

The gap itself is interesting. Male and female professionals start out even wage-wise when they enter the workforce. But a gap opens, persists and widens significantly for at least 15 years post graduation (when the wage gap gets to 15.6%). This can’t be good news to women or to the husbands who married them for their money.

Women Get a Lower Investment Return

The Yale study did a clever thing that had not been done before by comparing incomes of male and female PCPs versus those of male and female PAs over time. This was possible thanks to two large databases: the Robert Woods Johnson Community Tracking Physician Survey, 2004-2005, and the American Academy of Physician Assistant’s Annual Survey for 2005. Audiologists lack such databases and that is why we’re talking indirectly about us here by looking at medical doctors.

Paraphrasing the beautiful economic-speak of the Yale authors, an MD degree had a positive net present value NPV investment for most males but not for most females{{2}}[[2]](Post-graduate earnings/hour)*( hours worked) – school costs for most men,[[2]] The PA profession financially dominated medical school for most women but not men. In general, MDs of either sex had higher hourly wages than their PA counterparts, but the difference was much bigger for men: $25/hour for male MDs vs male PAs; only $16/hour in the female comparison.

Over time, male doctors’ incomes fully amortized their medical school expenses and outstripped the NPV of their PA counterparts. But female MDs did not fully amortize their education investment and would have had “marginally higher” NPVs had they gone the PA route.

How Come?

Several defensible reasons partially explain the existence of the gender wage gap in doctoring professions.

- Time on the job. Men and women came out of the chute at wage parity but men earned more on all the metrics after that. Part of the reason men got rewarded with higher pay is that they worked more hours — 14% more according to time panel data.{{3}}[[3]]Staiger DO. 2009. Comparison of Physician Workforce Estimates and Supply Projections. JAMA, 302(15). pp 1674-1680.[[3]] The Yale study demonstrates that 52% of the male/female doctor NPV gap goes away if they forced the assumption that women MDs “earned women’s wages but worked men’s hours.”

- Experience. Male PCPs accumulated 37,594 hours of experience in 15 years, on average. Women don’t get there for 19 years. The authors suggest that adjusting the wage gap for cumulative experience (males with 15 years of experience to females with 19 years) further reduced the actual gap.

- Full Time. On this metric, male and female PCPs are equivalent because both work at least 40-hour weeks. The difference lies above that number, where male PCPs aged 41-45 put in 11 more hours/week than same-aged female PCPs (56 vs. 45 hours). PAs, on the other hand worked about 40-hour weeks regardless of gender.

A not-so-defensible reason for the gap is that women work fewer hours because they are having and caring for children. Female doctors’ earnings decline significantly relative to male doctors once they have children, due to a decline in hours worked.{{4}}[[4]] Sasser AC. 2005. Gender Differences in Physician Pay: Tradeoffs between Career and Family. J Human Resources. 40. pp 477-504.[[4]] That moves the argument into a host of social policy discussions that are interesting, incendiary, complicated, and certainly beyond the scope of this blog.

What Do Women Want?

The authors’ speculations are also interesting and incendiary. They’re also hard to dispute. The first one does not surprise: women doctors are more likely to marry wealthier husbands, in which case they may gain incentives to reduce their work hours. It turns out that PAs are significantly more likely to be married before they start their degree programs than MDs. Perish the thought, but perhaps some women go to medical school to find a doctor to marry.

I like the second possibility — that women get advanced degrees despite incurring small financial disadvantages because they gain Utility by doing something “more interesting.” This serves as a reminder to readers that the fundamental economic concept of Utility has its roots in satisfaction and preference, not currency.

The third possibility is that people don’t know what they want to be when they grow up and going to medical school at an early age helps them figure that out. You’d think that would apply to men as well as women but that’s probably where the decision to get married and have kids is a game changer for some women professionals. PAs, on the other hand, start their programs 2 years later than MDs, on average. Perhaps those 2 years give them time to figure out what they want, or life has figured it out for them in the form of marriage and commitments.

Finally, the authors discuss the known finding that people systematically overestimate the number of labor hours they expect to supply and thus tend to “over-enter” markets. Again, you’d think this would apply to males and females, all things being equal.

Should She or Shouldn’t She?

This post focuses on medical education because that’s where the data are rich enough for economists to graze and find statistically significant relationships. But those findings have validity for women considering Audiology or other doctoral degree professions. Kevin Liebe, AuD, recently fired up the discussion in published articles on AuD education costs.

There are so many unanswered but economically important questions for those who are working in our field or considering it as a career. More than most, our profession is heavy on females. How many emerging female graduates are single but plan to marry and have children? How many graduates, single or married, expect to reduce or expand their labor hours in the future? When, if ever, do they see themselves retiring? How many see themselves as second income earners? How many see themselves as future caretakers for their parent(s) or other family members? What are their reasons for selecting Audiology as a profession in the first place?

Economically, it boils down to each female doing a self-examination of expectations and anticipations in order to forecast whether the graduate degree is a good or poor investment for her (and probably her parents). Harkening back to the Econ 101 posts, it’s important to remind readers that such evaluations are always made in terms of Utility and Opportunity Costs. The wannabe Audiologist’s rational consumption choice is supposed to maximize her Utility by a selective process in which she chooses the best opportunity available and within her budget. Does it?

There’s a lot more to talk about when it comes to Audiology, education and employment. I’ll bring some numbers to a future post and we can play around with them. In the meantime, I’d like to hear opinions and thoughts of readers and don’t forget that Equal Pay Day is coming up — April 9.

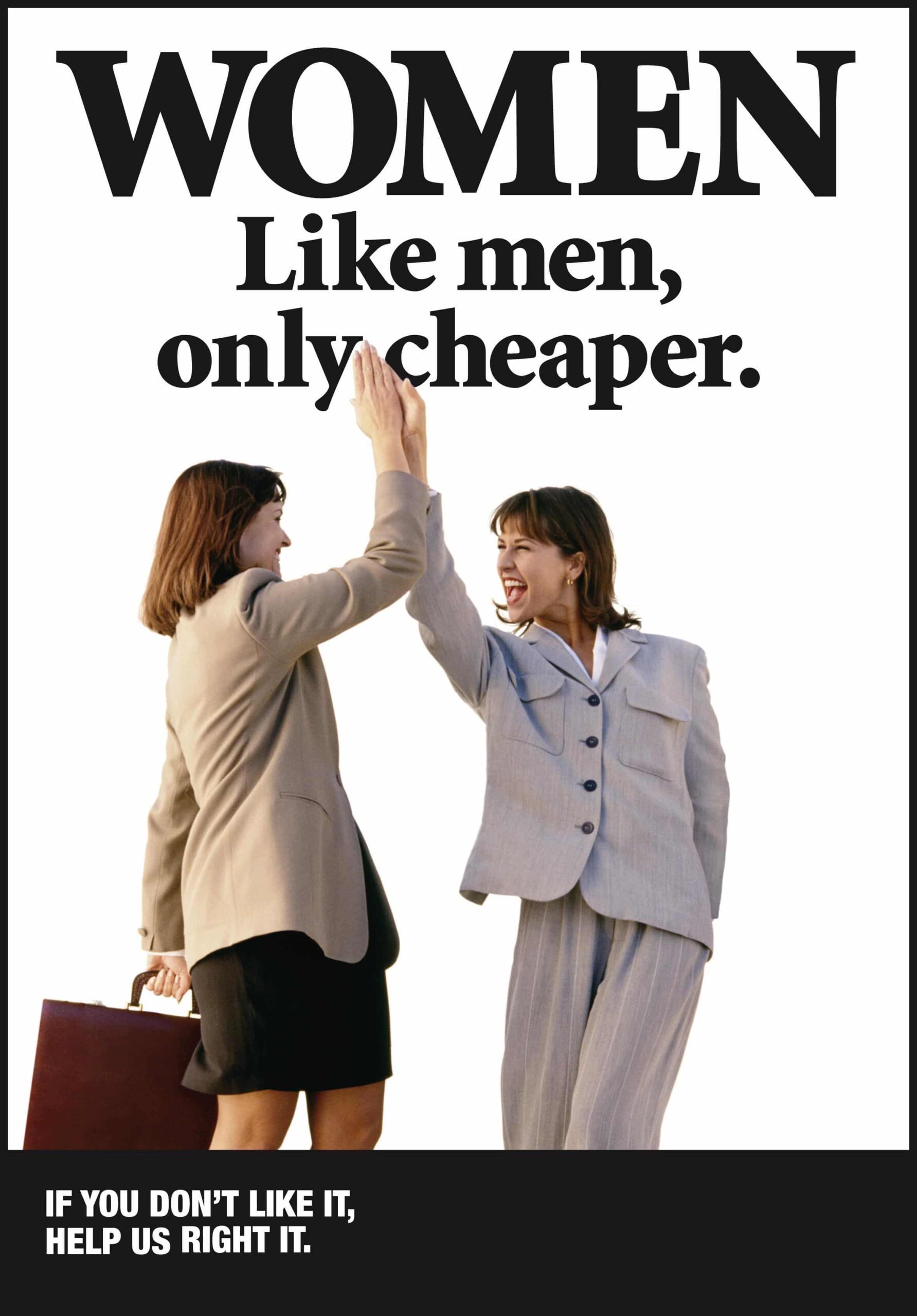

Photo courtesy of See Jane Run…the Show

Holly,

I don’t think ‘polite Audiology society’ will be able to ignore this one for much longer. Thanks for another thought-provoking article!

Compensation equity is always a fascinating topic. I think a more fascinating topic is an assessment of the value of an AuD as an entry level degree in terms of quality hearing health care. What is the expected impact on real world outcomes of being fit with hearing aids by an AuD versus an educated hearing instrument specialist who uses best practices? There are a lot of underemployed or unemployed psychologists, counselors and social workers earning a third of what audiologists make. I suspect they would love to be dispensers and do a great job since they already have the mindset to serve society. Is this perhaps a more affordable career path in hearing healthcare? Has the AuD entry requirement resulted in a severe reduction in qualified candidates for the future? One AuD I met lamented on the waste of time and money….she wishes she had become a board certified IHS with her liberal arts degree. She feels she would be making a lot more money and faster while delivering the same level of service. After all her internships did not include best practices such as REM and she was also asking my recommendations for validation!

Dear Anon: It is, indeed, a fascinating path to consider whether those with advanced degrees in counseling and psychology have thought about bringing their considerable — and apparently underused — skills to the hearing healthcare arena. I am not aware of the employment and compensation situations in those fields but it sounds as though you do. Do you know any psychologists, etc., who have considered the transition? if so, can you share their insights and opinions? Thank you.

Are there really an abundance of psychologists making $20k/yr? That’s pretty sad if it’s true!

I agree that patients would truly benefit if there were more professionals with a background in counseling, etc, rather than being sales driven as many dispensers have a reputation of being